Boobie Splat

How it once fed the world, and what replaced it.

First of all, get your mind out of the gutter!

We’re talking about these boobies.

I. The Motion of the Ocean = the Circle of Life

The Pacific Ocean contains two major systems of rotating current otherwise known as gyres. The North Pacific gyre rotates warm water from the equator clockwise towards the Arctic and cooler sub-arctic waters are thrown south, in particular along the Western coast of North America. The cold current which whisks along the coast, otherwise known as the California Current, is the reason for the North American West Coast’s rich and diverse marine life.

Similarly in the Southern Hemisphere, there is a second gyre, creatively named the South Pacific gyre. This system rotates counter-clockwise, thanks for the Coriolis Effect, sending warm water from the tropics south and cool water from the Antarctic region north along the western coast of South America. This current is known as the Humboldt Current, named after German naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt, although it’s often also called the Peru Current.

Both the California and Humboldt currents carry nutrient rich water. Much of the source of these nutrients comes from the death and decay of the ocean’s living creatures which post death fall towards the dark, cool, ocean floor. This decaying organic matter is brought to the surface by a process known as upwelling which brings this decaying organic matter into the habitat of hundreds of species of marine creatures that consume this nutritious soup. Several species of fish, who rely on this soup for food, end up being consumed by several species of sea birds including our friends, the boobies. These sea birds land, typically to nest, on the adjacent continental mass and islands. And like every other creature - these sea birds poop. This poop accumulates over the years in the same areas where these birds nest or rest. Thanks to the relative dryness of much coastal South America (home of the world’s driest non-polar desert - the Atacama) accumulates as opposed to washing off due from rainfall. Over hundreds, if not thousands of years, this poop accumulated into layers dozens of meters thick often covering up any of the actual landscape.

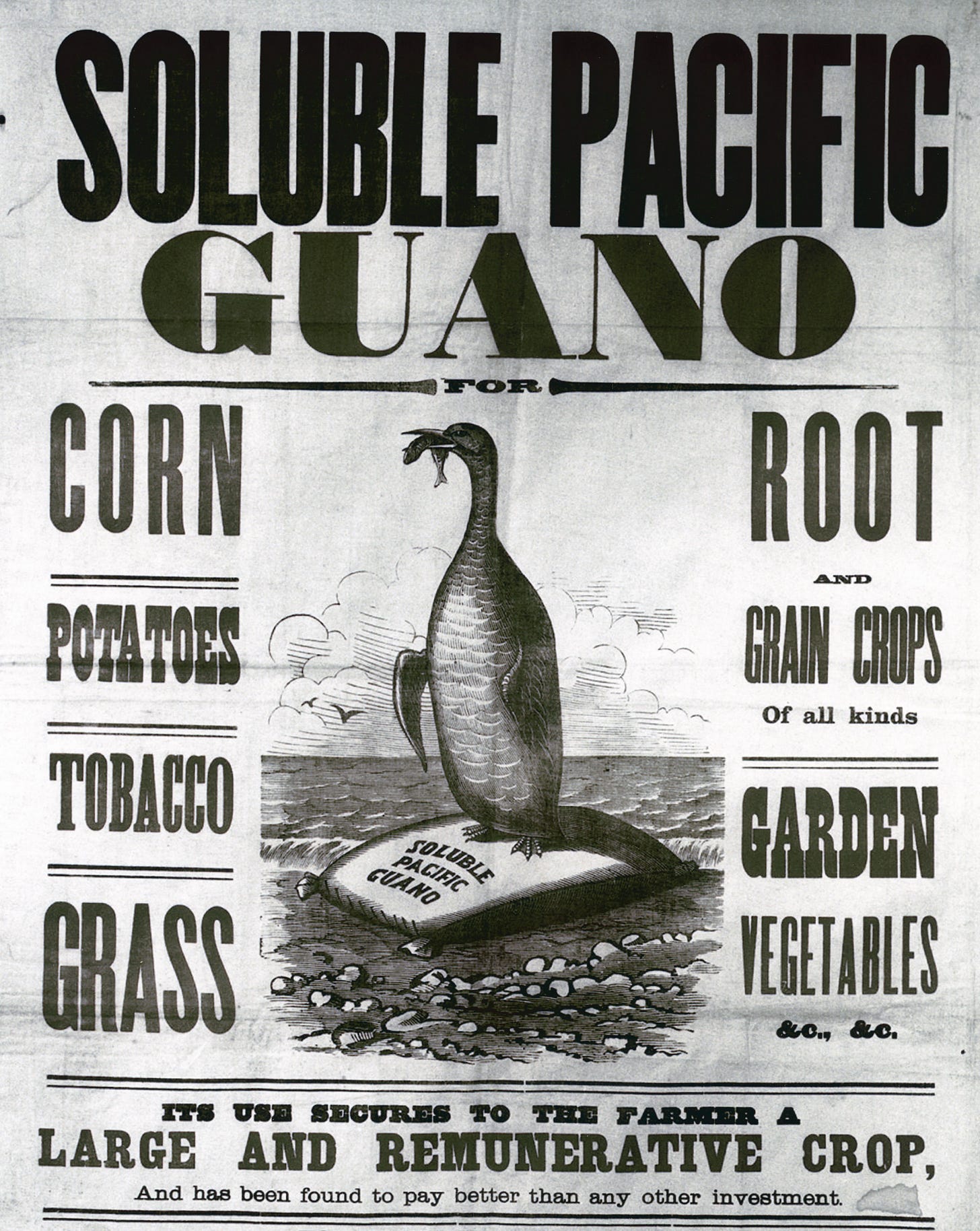

This waste also happens to contain an ample amount of three important substances: nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium which makes it an excellent fertilizer. Nitrogen is required by most plants for ample leaf growth, phosphorus for root, flower, seed, and fruit development, while potassium promotes water movement from root up-stem, flowering, fruiting, and solid stem growth. Nitrogen, despite being readily available in the atmosphere, cannot be absorbed directly by (most) plants due to the triple bond.

II. Feeding (Ancient) Empires

The Paracas civilization (900 B.C. to 400 A.D) used this bird waste as a fertilizer to successfully prosper in the deserts of what is now Northern Chile, Peru, and Bolivia. The Coastal Moche civilization used these deposits roughly 2000 years ago using reed boats to reach the sea bird excrement covered islands off the coast of what is now Northern Peru. The Wari, Tiwanaku, and Chimor civilizations (300 to 1150 A.D) who all spanned along much of the west coast of the continent used the substance as well. Most famous however was the rise of the Incan empire in the ashes of these groups, often by conquest.

The Inca may have been strangers to simple inventions such as the draft animals, steel, and even the wheel, but they make up for such in other domains. In particular, the Incans mastered agriculture to a degree few other pre-Columbian cultures did which allowed them to adequately feed their population and allowed for their empire to expand to become of the most advanced in the Americas.

The Empire spanned across multiple climates, from the deserts of the Atacama, to the Andean high altitude altiplano, lush valleys to even the Amazon tropics. Bringing glacial meltwater from the high Andes, the Incans irrigated arid areas with sophisticated irrigation systems in terraced fields sometimes obtaining three crop growth sessions per year in the same fields. They used llamas as small pack animals but the creatures were unfit to be ridden or drive a plow so all tilling of these fields were done by hand. Some farms in Peru and Bolivia are still tilled by hand to this day. A part of the Incan’s secret success as a well-fed empire was their use of this coastal bird waste. They called this miracle substance, wawa, but as with many indigenous loanwords to the future colonial languages, the spelling and pronunciation would later morph to guano.

Thanks to their use of guano and their sophisticated agricultural system, the Inca reportedly had between three and seven years of food surplus at some points in their history which is unprecedented in Pre-Industrial Revolution times. They became so reliant on guano that they eventually conquered the Chincha people who had the knowledge on how to build small sea-faring boats to access the guano-covered islands the Inca previously could not reach. The Inca even had a goddess, Urpi Huáchac, who represented the divinity of sea birds and sea life. Needless to say, they knew exactly where life came from.

If it wasn’t for guano, the large Inca Empire would collapse and the Incans themselves knew this. What is often described as the first example of animal conservation was developed by the Inca as they implicated measures to control and regulate the harvest and supply of guano to given areas. Harvesting guano was off limits during bird nesting season as to not scare the birds away or disturb their nests and the death penalty was imposed on anybody violating these strict rules.

The Spanish Empire eventually conquered the Incas and most other indigenous peoples of the Americas. For some strange reason, they did not jump on the guano bandwagon in their colonies nor back in mainland Spain but they did quickly bring tomatoes, tobacco, corn, and potatoes back where as they say - the rest is history. Guano didn’t pick up as a staple fertilizer again until the 19th century.

III. The Guano Age

It wasn’t until Alexander von Humboldt ventured to what is now Peru where he encountered local use of guano during his expeditions to the area. He brought samples back to Europe where chemists discovered it had high concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium - all vital nutrients for plant growth. Europe also had guano deposits but they were nowhere as concentrated or useful as fertilizer as the South American guano deposits due to a wetter climate which washed much of the excrement off wherever birds left it. The particular bird species in Europe also did not feed on the same species of fish either resulting in dropping of far lesser fertilizer quality. Humphry Davy, the father of electrochemistry, the first person to isolate elemental chlorine and iodine and among other things being the first person to isolate sodium and potassium, calcium, strontium, barium, magnesium and boron the following year wrote about Peruvian guano’s excellent fertilizing abilities in his book Elements of Agricultural Chemistry which was a multi-language best seller in the 19th century.

Things got really exciting with guano when the whaling industry expanded off the cost in the mid 1840s. These ships brought goods to Peru from Europe but left mostly empty. Their owners looked for a new product to ship and collaborated with Peruvian politicians and businessmen to ship guano. Peru later nationalized the resource allowing them to collect revenue on the export of the product. Peru also used the revenues to purchase the freedom of upwards of 25,000 Black slaves, and abolished the head tax on their indigenous citizens. Guano was primarily sent to the US, Britain, Netherlands, and Germany - all countries at the time experiencing unprecedented growth due to the Industrial Revolution along with desires for empire building - requiring arms. Guano also saw limited use as a source material for gun powder, although guano sourced from bats was often a better source and could be found in places outside South America. Prior to guano, rulers used to ask their subjects to preserve and give away as a tax their own urine and animals’ waste to the ruler for the purpose of creating gunpowder.

Guano extraction also played a key role in the United States’ desire for territorial expansion and imperialism too. The 1856 Guano Islands Act, which is legally still in effect today, “permits” US citizens on behalf of the United States itself, to seize unclaimed guano-topped islands. It also allowed the President of the United States to protect these claims using military force and placed these islands under legal jurisdiction of the US. Several notable islands in both Pacific and Atlantic were acquired via the Guano Islands Act including Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnson Atoll, and Midway Atoll. A few islands - Navassa, Bajo Nuevo, and Serranilla remain in territorial dispute to this day with Haiti , Colombia, and Jamaica.

Unlike the age of the Inca, the Peru-European/US guano trade resulted in near depletion of several notable guano sites, especially the Chincha Islands, which had been a large source of guano dating back to pre-Incan days. Extraction moved to other islands and eventually to salitre or saltpeter, a mineral and an entirely different substance than guano that contains large quantities of sodium nitrate - also a great fertilizer. Saltire was primarily sourced from the Atacama Desert from the mineral caliche - originally ancient seabed since lifted onto the continent as part of the world’s driest non-polar desert. This region at the time was mostly within the territorial boundaries of Peru and Bolivia and part of Chile. Saltire also contains potassium, another important nutrient for crops but was also a key ingredient for gunpowder at the time. The British for example largely colonized Bengal specifically for their large salitre deposits.

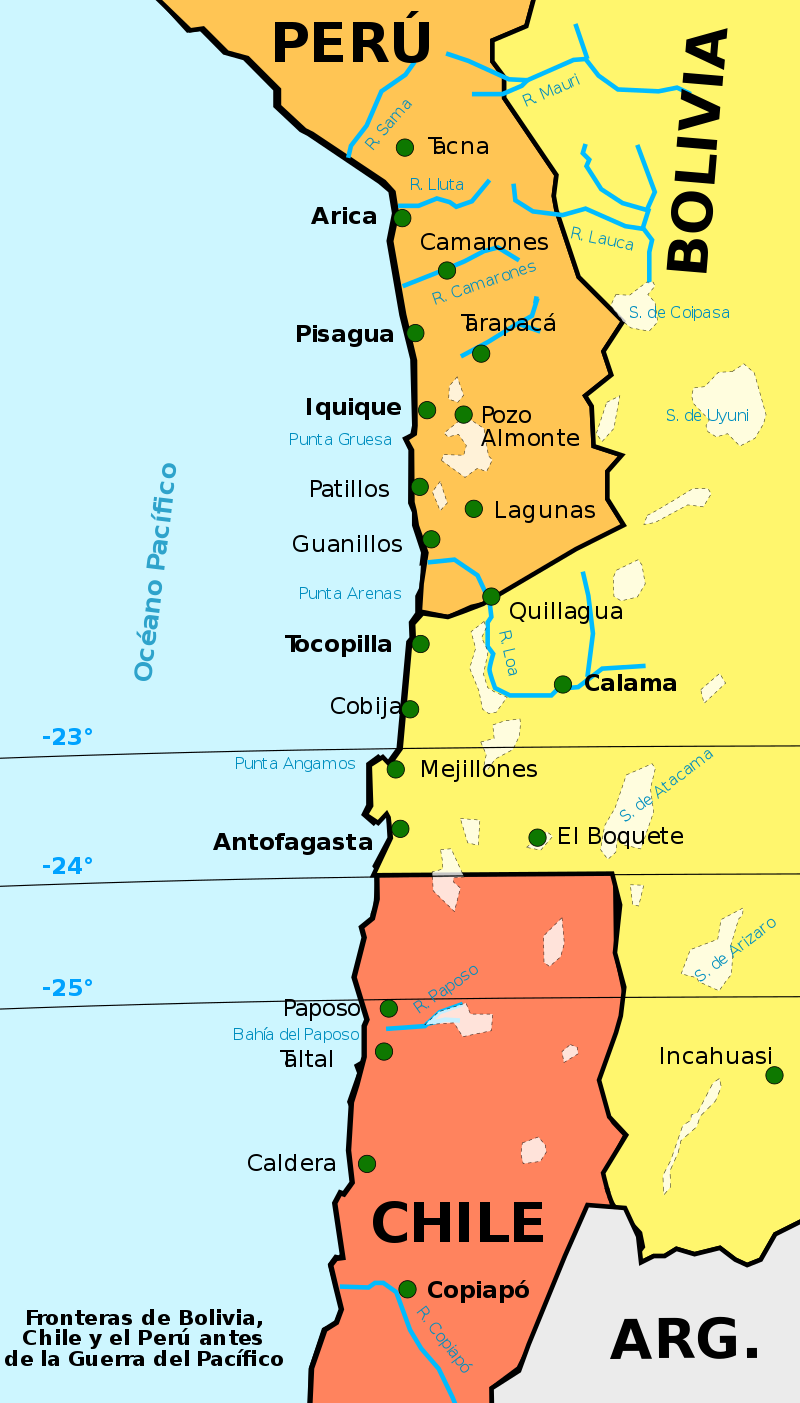

Peru, the world’s primary source of guano, also took another loss by the invasion of Chile during the War of the Pacific (often called the Saltpeter War) between 1879 and 1883. The Chileans wanted both the saltire and the guano deposits for themselves and had a extraordinarily strong Navy for a country of its caliber at the time. The majority of the workers in the mining operations were also Chilean increasing the desire for their own government to seize these areas for Chile herself. Despite the name, the war was also fought largely off the coast - in the interior of the Atacama desert and even in the Andean highlands. In 1883, Chile and Peru signed a treaty followed by a truce between Chile and Bolivia in 1884. Chile acquired the former Peruvian territory of Tarapacá, and the Literal Department of Bolivia, which was their only coastal jurisdiction. The boundaries of the three countries were not officially agreed upon until the Treaty of Lima in 1929. Bolivia, despite being landlocked today, continues to maintain a navy but her ships only sail Lake Titicaca, a large high altitude lake straddling the modern border of Bolivia and Peru. The loss of coastal territory is to this day also a contested issue between Chile and Bolivia and is blamed for one of the reasons Bolivia remains relatively less wealthy than Peru and Chile.

IV. Better Living (and Horrific Killing) Through Chemistry

“England and all civilized nations stand in deadly peril of not having enough to eat. As mouths multiply, food resources dwindle. Land is a limited quantity, and the land that will grow wheat is absolutely dependent on difficult and capricious natural phenomena... I hope to point a way out of the colossal dilemma. It is the chemist who must come to the rescue of the threatened communities. It is through the laboratory that starvation may ultimately be turned into plenty... The fixation of atmospheric nitrogen is one of the great discoveries, awaiting the genius of chemists.”

Sir William Crookes , Presidential Address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science 1898.

With the dual demand for both fertilizer and gunpowder, the easy and abundant guano and salitre deposits were diminishing quickly. In 1898 British chemist Sir William Crookes spoke about a potential global famine he coined the “wheat problem,” unless alternatives to Chilean salitre (and guano) could be found, this famine would sweep the global population by 1930. Sir William Crookes suggested the only way to alleviate this issue was to figure out how to artificially synthesize the existing nitrogen from the air.

It wasn’t just a hungry and arms-obsessed Britain that realized the impending doom. Germany, also experiencing record population growth and empire expansion thanks to the guano and saltire trade also noticed. The Germans were importing ever more saltire from Chile, and grew concerned the British or others could cut off that supply especially after the British declared war with the Boers of South Africa - a region colonized and occupied by Germans and Belgians.

“It may be that this solution is not the final one. Nitrogen bacteria teach us that Nature, with her sophisticated forms of chemistry of living matter, still understands and utilizes methods which we do not yet know how to imitate.”

-Fritz Haber

The first notable German to try to tackle this problem was Wilhelm Ostwald, who unlike others, experimented using chemical reactions instead of newfangled electricity to create ammonia (NH3) - which could be used as fertilizer identical to guano or salitre. Carl Bosch, an employee of German chemical magnate BASF, was interested in Oswald’s experimentation and verified that unfortunately Oswald’s attempt was largely unsuccessful. Fritz Haber tried as well, coining the process, “bread from the air.” BASF managed to give him a laboratory and partial profits from the sale of any future product to try to figure out this process. BASF’s labs allowed Haber to experiment with different catalysts and higher pressures (turns out ammonia needs very high pressures to stay “together” for the lack of a better term). In a tale with parallels to Thomas Edison’s attempt of trial and error using thousands of different filaments for lightbulbs, Haber faced similar difficulties with chemical catalysts. He discovered that osmium, a rare element at the time, worked and produced small amounts of ammonia. Bosch, still with BASF, continued this research into different catalysts and even bought most of the world’s known supply of osmium at the time.

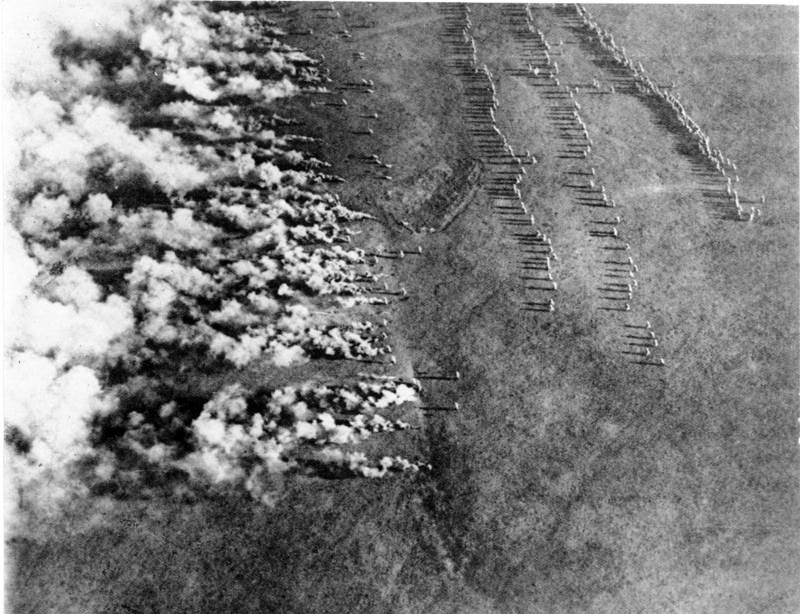

BASF had something resembling a working process by 1911 although it was still more expensive than mining and shipping of saltire from overseas. By the time the first World War started, Germany believed it would be a short war - something their stash of salitre could handle. But the Brits sank several German ships along the salitre trade routes so in fear of both an unarmed military and a starving population, they began throwing everything they had -both the highly inefficient electric-based processes and the chemical based processes to produce ammonium. Bosch turned things up past ten by 1914 by scaling up two different plants using a new catalyst. Many German chemists, in part in support of the war, were intensely ideological and loyal to the German state. Haver himself signed onto the notorious Manifesto of the the Ninety-Three, a document signed by top scientists, academics, activists, and intellectuals in support of the war. Haber also helped develop several non-ballistic weapons otherwise known in today’s world as chemical weapons. He also personally presided over the first ever use of chemical weapons in history during the German invasion of Belgium.

This process of fixing nitrogen from the air is today famously known as the Haber-Bosch process, and has become more efficient over the years. The primary feedstock changed early on from coal gases to natural gas (methane). Today not only does the Haber-Bosch process produce the majority of the world’s fertilizer but it’s cemented both natural gas and the end product, ammonia as modern staples few in society can live without.

The basics are to take air, which composes of roughly 78% nitrogen packed in difficult to break triple bonds, water, and hydrogen sourced from natural gas. Together this mixture is compressed and injected into a tank containing a catalyst. Ammonia in the form of a high temperature gas is produced as a result of the chemical reaction. Carbon dioxide is also produced. Both products are cooled, in the case of ammonia into its final liquid state. The carbon dioxide is used in the food shipping industry - particularly for freezing goods.

Both Haber and Bosch won Nobel prizes for their achievements despite Haber’s, uh contributions, to Germany’s notorious introduction of chemical warfare in the First World War. The development of ammonia via the Haber-Bosch process is blamed by some historians too as having prolonged the duration of the war.

On a better note, between this invention and the innovations of the Green Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s spearheaded by Norman Borlaug, the world’s population has not only continued to grow but humans have managed to grow more food of better quality on less land. The areas previously exploited for guano and saltpeter see very little mining these days. Many of the guano islands off the coast of Peru are seeing a re-growth to their natural state. It’s also argued among some that the handful of seabird species such as Peruvian boobies were also saved from significant population decline or extinction.

Nothing is without tradeoffs, however. On top of the chemical weapons background of some of the German scientists, anthropogenic nitrogen as it’s called has led to increased emissions of nitrous oxide, groundwater and surface water contamination, and the notorious “Dead Zone” in the Gulf of Mexico. Traditional farming methods were also sidestepped by modern industrial agriculture which includes in many areas notorious single crop plantings without rotation and of course, crop monocultures.

V. Stomach Pains

To keep the chemistry lesson as simple as possible, you need natural gas to produce ammonia and energy from fossil fuels to mine for phosphate. You need ammonia and phosphate to make fertilizer. You need fertilizer to grow food at scale. You need food to keep the peace.

- Doomberg in Starvation Diet

Fast forward to the early 2020s, there’s not only an energy and inflation crisis - both not seen in such magnitudes in much of the world since the 1970s but several notorious downstream effects. In particular for this piece, fertilizer shortages leading to record high prices are striking various areas of the world. The United Nations World Food Program states the world, particularly the developing nations, is now facing the worst food crisis since 2008. (It should be noted the same UN, also is a huge contributor to the problem itself.)

Sri Lanka, reversing decades of development and progress brought to the island nation (in large part thanks to the Green Revolution and Haber-Bosch produced fertilizer) collapsed this summer after a ban on all artificial fertilizers. Farmers were forced to use so-called natural fertilizers such as cow and chicken manure which contain far less usable fertilizer and nutrients for crops. This, predictably, slashed their yields and contributed to massive civil unrest resulting in a collapse of the country.

“It's a free society. But don't tell the world that we can feed the present population without chemical fertilizer. That's when this misinformation becomes destructive.”

– Norman Borlaug

Only a handful of countries produce fertilizer at scale and it’s only wealthy countries who can afford to subsidize their farmers during times of high prices or supply shortages. Developing and poor nations suffer the most resulting in farmers simply giving up on the high price of fertilizer. In late summer of 2021, China even banned all exports of phosphate, another important fertilizer to ensure they were able to feed their own population first. Britain bailed out their top fertilizer producer and faced shortages of CO2 in their frozen food supply chain. (Try to imagine a grocery store without a frozen and refrigerated foods section!) Given the absolute necessity of natural gas as a feedstock for making fertilizer (among other things), the increasing prices along with the desire by global elites and unserious people to “end” fossil fuels have only exasperated the issue. There is simply no sustaining of the current global population without these fertilizers.

That was all before the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Belarus and Russia are both large exporters of fertilizers, particularly potash. Ukraine is the bread basket that provides wheat to several African and Middle Eastern countries. Western sanctions against Russia (which don’t officially start until next month) and a general re-alignment of global powers (BRICS, Saudi, etc) are upending the old world order too. Nations will rush to secure the food supply for their own people before being generous by supporting others. Add the absurdity that less and less land is being made available for growth of crops for human or livestock consumption and instead for renewable diesel which is seen as the “green” alternative to traditional oil-derived diesel.

The shoreline and islands of Peru, where the guano trade once flourished, is even seeing a resurgence in guano extraction by Peruvian farmers priced out of the traditional fertilizer market. Earlier this year thousands of Peruvian farmers and truckers went on strike placing much of the country to a grinding halt too.

The Peruvian Government even christened a special ship to move the stinky wannabe gold from the islands to the ports. While a repeat of the near global rush for Peruvian guano is unlikely, there are a few million more Peruvians than there were 150 years ago and the opportunity to reverse the restoration the the guano islands, coastlines, and sea bird habitat is arguably under threat. But ultimately Peruvians, let alone any population, when faced with hunger is going to do what they need to do in the short term. Damn the environment.

That ship, by the way, is aptly named Pelicano, or Pelican after the very birds whose thousands of generations of dropping contributed to the region’s wealth over 150 years ago and changed the world.

Fascinating history. Thanks for posting this!

Brilliant work. Explains wonderfully how interconnected everything is and how fossil fuels permeates almost every aspect of life. People are in for a big shock when they realise.