Finding a Voice in Colorado's Electricity Sector

Colorado's PUC Structure Fails to Account for the Uniqueness of the State's Grid, it's People, and Overall Reliability

Colorado’s Confusing and Unique Grid Setup

Colorado doesn’t have a unified grid. Instead it’s divided into two major interconnections: the Eastern Interconnection, which spans most of the state and connects to the Northeast and Kansas, and the Western Interconnection, which covers parts of western Colorado and connects to utilities in Utah, Wyoming, and California.

This geographical division complicates the state’s grid management, as coordination between these two interconnections is limited. This lack of coordination affects both the reliability and cost of the grid especially as the state mandates require the state go go full steam ahead with the whims of the Church of Carbon, a term attributed to the great Doomberg.

Some of the state’s utilities, most notably Xcel Energy operates under the traditional vertically integrated monopoly, while others operate in full RTO membership or partial RTO membership.

Full RTO participation is with the Southwest Power Pool (SPP) but several utilities including municipal ones are exposed to SPP in somewhat of a hybrid form with their participation in SPP’s Western Energy Imbalance Service (WEIS) Market including Colorado Springs Utilities and the Platte River Power, the generation provider for the cities of Fort Collins, Loveland, Longmont, and Estes Park. In other words, customers of these local utilities are also exposed to the RTO Meredith Angwin mentions in Shorting the Grid and they likely don’t even know it. (I did not)

The lack of a unified RTO presence creates inconsistencies in how electricity is priced, dispatched, and transmitted across the state. While full RTO membership offers some benefits in cost management and regional planning, it can also expose ratepayers to price spikes and loss of local control. Partial participation, as seen with the WEIS market, provides some grid efficiency benefits but lacks the comprehensive oversight of a full RTO.

The Colorado Public Utilities Commission (PUC) is responsible for regulating the state’s investor-owned utilities, including Xcel Energy, ensuring that electricity remains reliable and affordable. However, the PUC’s authority is limited in areas already under full RTO participation, where market-driven mechanisms dictate pricing and resource allocation. In these regions, the PUC has less direct control over transmission planning and energy procurement, as those functions fall under the governance of SPP.

In contrast, in areas outside of full RTO participation—such as those served by Xcel Energy—the PUC has greater influence over resource planning, rate approvals, and infrastructure investments. This creates a regulatory imbalance, where utilities operating outside an RTO are subject to stricter state oversight, while those in an RTO follow broader market-driven policies.

The Role of a PUC

Electric utilities are natural monopolies, meaning that it is generally inefficient to have multiple companies building competing electricity grids in the same geographic area. Instead of allowing competition, states (theoretically) regulate these monopolies through their Public Utility Commissions (PUCs) or similar bodies to ensure fair prices, service reliability, and public accountability. PUC decisions impact electricity rates, energy sources, grid reliability, and infrastructure investments for those under their regulatory control.

From the Customer/Ratepayer’s Perspective, PUCs are supposed to protect consumers by regulating electricity rates and ensuring service reliability. They approve expenditures, set fair rates, and oversee new energy infrastructure projects. However, their effectiveness in representing customer/ratepayer interests varies by state. Some legislatures direct PUCs to prioritize affordability, while others focus on broader goals like reducing greenhouse gas emissions or integrating renewable energy.

Meredith Angwin,in Shorting the Grid: The Hidden Fragility of Our Electric Grid, argues that customers often have limited influence in PUC decisions, especially in Regional Transmission Organization (RTO) areas where insider-driven governance can make the system less transparent. She points out that ratepayer representatives often hold only a small fraction of the voting power in key decision-making committees, meaning large utilities and industry players dominate the regulatory process. This, as she explains in her book leads to higher costs and a less reliable grid.

Additionally, despite being called “customers,” most ratepayers in regulated states and RTO areas have no real choice in their electricity provider. They are bound to the rates and policies determined by PUCs and utility companies, limiting their ability to shop for better service or prices.

From the Electric Utility’s perspective, PUCs act as both gatekeepers and business enablers. They approve infrastructure projects, set rates, and enforce regulatory compliance. In vertically integrated markets (where utilities own both generation and distribution), PUCs historically allowed utilities to earn a regulated rate of return on their capital expenditures (new lines, substations, generating stations, etc..), incentivizing them to build more infrastructure—even beyond what was necessary—because it increased their profits. This same regulated rate of return is in large part today why electric utilities are so obsessed with renewable energy rollouts.

Utilities also develop close relationships with PUCs, leading to regulatory capture, where commissions favor the interests of utilities over ratepayers. As Meredith Angwin explained in Shorting the Grid:

A state regulatory agency had to approve the expenditure. Depending on the state, this agency was usually called the Public Utilities Commission (PUC) or the Public Service Board (PSB). At the state level, utilities tended to get a little cozy with their regulators (“regulatory capture”). Overbuilding and overcharging customers was often the result. On the other hand, the utility had incentives for building a very reliable grid.

In deregulated RTO areas, utilities have different incentives, as they must compete in energy auctions rather than simply passing costs onto consumers through a regulated rate structure. These auctions often benefit insiders and do not always result in a more reliable or cost-effective grid.

PUC commissioners, who lead these regulatory bodies, are either appointed by governors or elected by voters, depending on the state. Their backgrounds and selection processes influence their regulatory approach. Some states require commissioners to have specific expertise in energy, law, or economics, while others allow for more politically driven appointments. The philosophy of a commission—whether it leans toward market deregulation, environmental goals, or consumer protection—shapes the policies utilities must follow.

The nuances of how each state runs and appoints their PUC is explained in this in-depth article “Utility Commissioners: How They’re Selected, What They Do, and How They Impact Daily Life” by Emily Apadula, but here we’re going to focus on Colorado.

Colorado’s PUC: Filled with High Priests for the Church of Carbon

Colorado’s current PUC governance structure consists of three Commissioners, all appointed by the Governor and approved by the State Senate. One caveat is that no more than two of these commissioners can be from the same political party from theoretically dominating the agendas of the PUC. But this setup still makes the PUC highly susceptible to political influence, often favoring policies aligned with the governor’s energy agenda rather than prioritizing reliability and cost-efficiency for ratepayers.

The current commissioners, all appointed by current Colorado Governor Jared Polis, have professional backgrounds heavily focused on renewable energy and environmental policy:

Chairman Eric Blank (Denver): Appointed in 2020, as the co-founder of and former president of Community Energy Solar along with former executive VP of Iberdrola Renewables, Charman Blank has experience in renewable energy and clean power markets. His focus on decarbonization aligns with state policy goals but this raises concerns about prioritizing sustainability over affordability and reliability.

Commissioner Megan Gilman (Edwards/Vail): Serving since 2020, Gilman has a background in mechanical engineering and energy efficiency consulting. While technically knowledgeable and the only one with a background in rural needs with her former participation with the Colorado Rural Electric Utilities Association, her focus has been on clean energy transitions rather than balancing grid reliability.

Tom Plant (Boulder): Appointed in 2023, Plant has a history in environmental advocacy and renewable energy policy. His appointment further solidifies the state’s Luxury Belief/Church of Carbon commitment to aggressive renewable expansion, even at the potential expense of grid stability or affordable prices. Plant is the one nominally non-partisan member but served in the past in the Colorado House as a Democrat. He also worked under former CO Governor Bill Ritter and prior to his appointment worked under Ritter again at Colorado State University’s Center for the New Energy Economy.

The PUC’s current structure in other words lacks ideological and geographical diversity, with all commissioners aligned toward aggressive decarbonization rather than a balanced approach that includes affordability and grid security.

It also lacks geographical diversity with two of individuals being from either the Denver Metro area and the other from the resortified and gentrified Vail.

Further, it lacks someone with a background in energy sanity and/or consumer advocacy which are both domains a PUC really needs. Each of these Commissioners arguably have huge conflicts of interests in their professional lives and in their professional networks.

Potential Reform

Even without these facts or under a different leadership and ideology, a three-person Commissioner setup appears inadequate to represent the diverse interests of the people of Colorado.

This is where HB25-1126 Public Utilities Commission Membership Geographic Representation comes in, scheduled to be heard tomorrow afternoon in the House Energy and Environment Committee.

HB25-1126, much like the state’s past nuclear energy bills is a bipartisan effort. If passed, and it has a long way to go until reaching the Governor’s desk, it would increase the size of the PUC’s Commissioners to five still maintaining the partisan requirement but this time expanded to only three of the same party. The expansion in the representation would need to be geographical based too with one from the Western Slope, another from the Eastern Plains, and a third representing the Denver/Front Range Metro area.

The hearing is likely to be attended by electric power industry, green non-profits, and lobbyists for both groups and few, if no every day Coloradan.

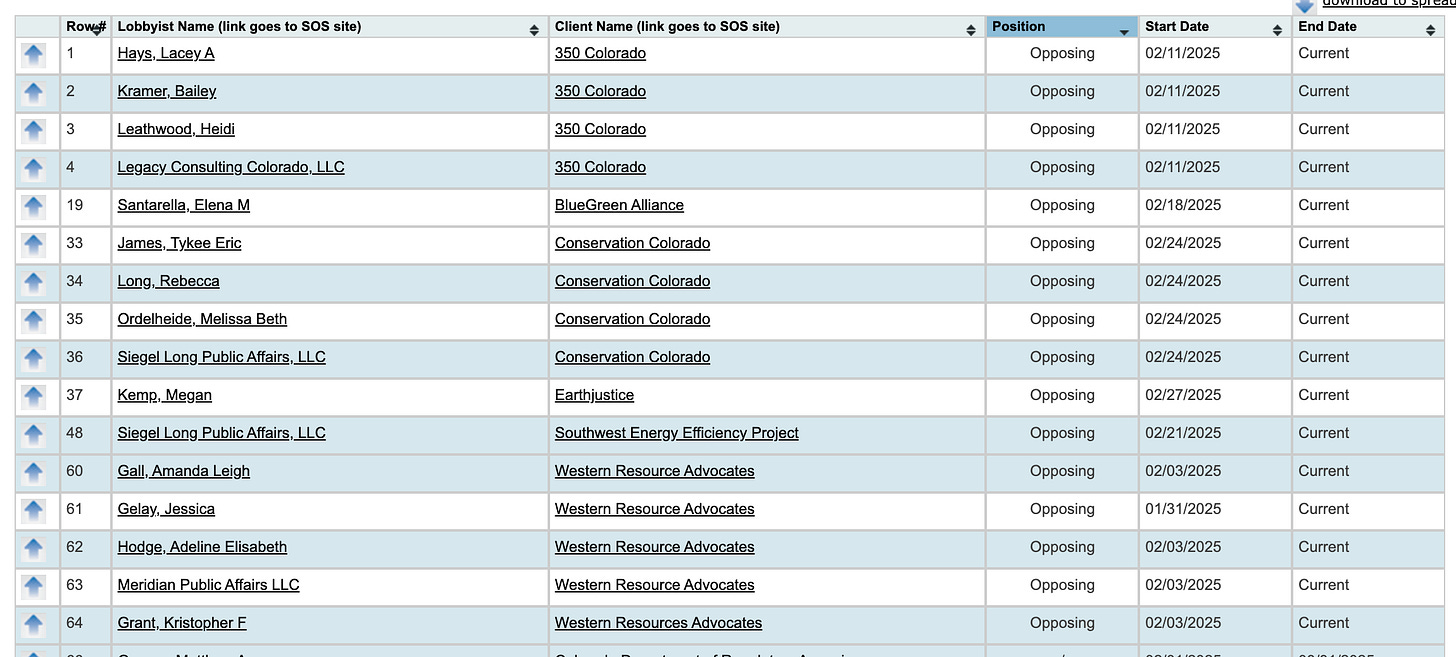

As shown by the Colorado Capitol Watch, who sources their data from the Secretary of State, all of the registered lobbyists in opposition are Church of Carbon groups making it evident should this bill pass, their unequal influence on with the Colorado PUC will be curbed.

It’s important that individuals with professional dog in the fight speak up - especially those who live in the territories served by the two major IOUs that serve the state, Xcel Energy and Black Hills Energy as they’ve been the ones seeing the brunt of the increases in their electric rates.

A link on how to testify is here and Colorado residents can find out who represents them here.

Robert Bryce is fond of saying, “I’m not a Democrat. I’m not a Republican. I’m Disgusted,” and roughly half of Colorado’s registered voters are registered as unaffiliated likely resonate with Bryce’s perspective. And as Meredith Angwin wrote in the closing chapter of Shorting the Grid, “local control of the local grid works best.”

Great read! We need to break the regulatory capture by the eco-left (Remember Eric Blank was the ED of Western Resource Advocates) and monopoly utilities, in particular Xcel, which happily decarbonizes because they can pad their asset base. One of the worst things Polis has done is abandon the tradition of having a voice of reasonable opposition. By appointing an "unaffiliated" who is probably farther left than the other two, there is no one to check the progressive left's worst instincts on generation, transmission, distribution, and cost. The current PUC is just a rubber stamp. They only meet on Zoom, so they in-person public comments. For sound energy policy that delivers reliable power at the least cost, we MUST have diversity on the PUC.

Whoops. Darn fat thumb. Anyway, I think we also need to be wary of regulatory capture by the industries that are being regulated and whose main objective is shareholder profits. There must be a middle way between the Church of Carbon and the Church of Capitalism.