Just Bury It

Why Don’t Utilities Just Underground Everything?

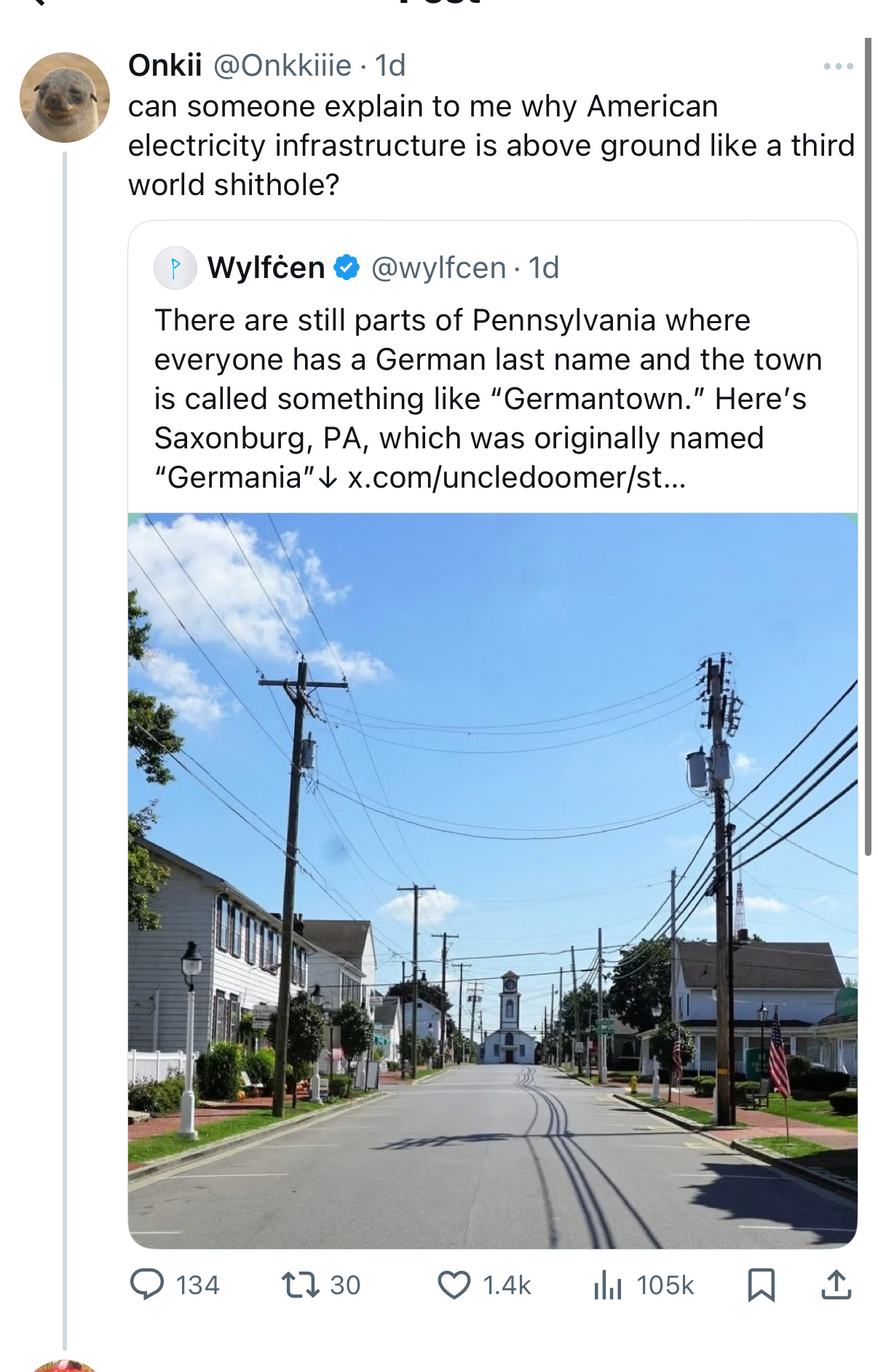

This post recently mocked U.S. electrical infrastructure as being “above ground like a third world shithole” alongside a photo of Saxonburg, Pennsylvania.

First of all, if this poster is claiming what’s shown in the photo is “third world,” he or she has clearly never been to such a place. The lines in this photograph are a dream compared to just other parts of the United States and “third world” utility infrastructure.

It’s also an example of cherry picking.

One can go to different parts of the United States and find far worse lines or areas where all the infrastructure is completely underground or something in between. New developments in the United States tend to require underground construction anyways.

One can also go to the “third world” and find a complete rat’s nest in one area, but “first world” underground utilities in another. Both Japan and South Korea, considered “developed nations” have “third world” rat’s nests of overhead utilities even in their wealthy capital cities. It’s no different in Enlightened Europe.

But to not get too off-topic here - the key question here is - why don’t utilities just go underground?

Money Money Money

The primary barrier is money.

Undergrounding existing infrastructure is dramatically more expensive than overhead construction, especially for existing overhead infrastructure. For electric distribution lines—the wooden-pole systems that feed houses and small businesses, burying cables typically costs five to ten times more than stringing them overhead. For transmission lines—the large corridors that carry bulk electricity—costs can be ten to twenty times more at high voltages.

Now imagine applying those multipliers to an entire city or state’s infrastructure. A utility with 10,000 miles of distribution line could be looking at a price tag in the tens of billions.

Because utilities recover costs through customer bills, those billions would show up in monthly electric rates. In states where rates are already politically sensitive, regulators almost never approve undergrounding projects unless there’s a compelling reliability case. For most communities, paying three, five, or ten times more just to hide the wires and cables isn’t worth it.

For electric utilities owned by a government, such as a municipality, the costs must be passed down onto the citizens via either increased rates or the city taking on debt though bonds.

Pole Ownership and Attachments

Another overlooked issue: utility poles, especially at the low-voltage distribution level, don’t just carry electric power. They carry telephone, cable TV, fiber optic internet, and sometimes municipal or emergency services lines. The photograph in question at the beginning of the post shows this mixed ownership of the assets on the pole.

And they’re not all owned by electric utilities. In some cases, the power company owns the pole and leases space to telecom companies. In other cases, telecom companies own the pole, and the utility is the tenant. Some areas are even more complicated with the electric utility running on its own lines separate from the communication lines in two separate rights of way. In the United States, The Federal Communications Commission regulates these pole attachments and sets rules for access and cost-sharing.

Burying lines would require all parties—electric, telecom, cable, internet—to coordinate construction and share costs when they all share the same pole line. That’s far more complicated than one utility deciding to bury its own wires.

Disputes over right-of-way, ownership, billing, and liability can drag on for years, delaying projects. A common saying on the electric side is that “communication companies don’t communicate,” indicating the truism that communication companies run on their own schedules. We in the electrical world despise communications companies not just for that but for their blatant and repeated violations of safety code and tendency to abandon unused communications lines on the poles creating safety and aesthetic hazards. Communication companies often attach to electric lines without running any type of structural analysis to see if their lines overload the poles too. The electric utility may indeed get the green light to underground but they have to leave saw-ed off poles with the existing communications cables intact and it’s the responsibility of these communication companies to remove the pole stubs.

Other countries avoided much of this by centralizing electric and communications under state monopolies for decades. The U.S., with its fragmented ownership and regulatory structure, faces far more obstacles.

Europe sometimes gets held up as the model of underground utilities. But context matters. After World War II, many European countries rebuilt entire cities almost from scratch. When streets were already rubble, burying utilities was relatively easy to integrate into reconstruction. They also had state-owned monopolies for both power and telecom. In France, EDF could bury lines without negotiating with half a dozen private companies. In Spain, Telefónica and the state grid could coordinate trenching. Costs were often covered by taxpayers rather than passed directly to ratepayers.

The U.S. never had that reset moment. By the time suburban sprawl spread across the country in the mid-20th century, overhead poles were the fastest and cheapest way to electrify millions of homes. Scale mattered: America was building a continental grid, not rebuilding compact nations.

Rights-of-Way and Property Connections

Most utility poles sit on narrow strips of public easement along roads. To bury them, utilities must trench or bore directly under streets and sidewalks where there is often existing water, sewer, or gas lines. That means closing traffic lanes, tearing up pavement, and disrupting local life for months.

But the real sticking point is service drops—the individual connections from the pole to each home or business. Converting overhead drops to underground requires trenching across private property, cutting through lawns, driveways, and landscaping. Property owners may be on the hook for part of that work.

I’ve experienced this myself. A communications company recently ran underground fiber down my street. This locally-owned and operated fiber optic company offers high-speed broadband with speeds that blow the cable company (cough, Comcast) out of the water at a better price and with actual customer service.

I’d love to connect to it, but to finish the hookup I’d have to pay several hundred dollars out-of-pocket for them to trench into my yard. On top of that, I’m in my final year of renting. I’d need permission from the property owner and the HOA.

Material, Labor and Workforce Specialization

Overhead and underground materials are also two different animals. Overhead wires, switches, transformers, regulators, etc, are completely different animals from those used for underground infrastructure. Utilities have to keep extra stock of everything they use on their system and the industry is currently experiencing supply chain shortage issues. There’s also the issue of private utilities trying to squeeze the value out of their assets through depreciation on their balance sheets.

But cost isn’t just about materials—it’s also about people. Overhead and underground systems require different skill sets and crews.

Overhead lineworkers are trained to climb poles, operate bucket trucks, and splice aerial conductors while working “hot” on energized lines. Underground crews are trained in conduit systems, vaults, and high-voltage cable splicing in confined spaces. The protective gear, tools, and procedures are completely different. A lineman who can safely replace a transformer on a pole isn’t automatically qualified to diagnose a fault in a 13 kV cable in a manhole or vault.

For utilities, this means maintaining parallel workforces. If you serve an area with both overhead and underground infrastructure, you need two different teams, with two different training pipelines, and two different sets of specialized equipment. Underground labor is often slower and more expensive per mile because it involves excavation, confined space safety, and complex splicing procedures.

Reliability Trade-Offs

A common argument for undergrounding is reliability: no poles to fall, no trees to take out lines, no ice to weigh down conductors. And that’s partly true—underground systems are less vulnerable to weather.

But they have their own problems. Faults are harder to detect and repair. When an overhead line breaks, the cause is usually visible—a fallen tree, a broken pole, a snapped wire. Crews can locate it quickly and fix it in hours. Underground faults are invisible. Finding the problem often requires specialized testing, digging, or excavating along the line. Repairs can take days.

This is why utilities often prefer a hybrid model. Long feeder lines remain overhead for easier access, while underground laterals serve downtowns, new subdivisions, or high-value commercial areas. That way, reliability is balanced with maintainability.

It’s also why undergrounding isn’t a magic bullet for storm resilience. After hurricanes in Florida, utilities found that buried lines fared better against wind—but flooding created a new set of failures.

Overhead and underground each have vulnerabilities and trade offs.

So, why not just bury it?

When you add it all up—money, ownership, rights-of-way, labor, materials, and reliability—the answer becomes obvious. Undergrounding has its place, but it’s not a universal solution. It costs significantly more than overhead construction, requires parallel workforces and supply chains, creates property access headaches, and brings its own reliability issues.

So the next time someone looks at a neat set of poles in Pennsylvania and sneers about “third world” America, maybe they should ask themselves a few questions first:

Do you really want your electric bill to triple just so the wires disappear from view?

Are you ready to have your street torn up for months—and your front yard trenched—for aesthetics?

Do you understand that even Tokyo and Seoul still live with “third world” tangles of wires in their wealthiest districts?

And do you realize that the U.S. still runs the most reliable large-scale grid on earth, poles and all?

If the answers are no, then maybe the problem isn’t the poles, it’s the utopian, trade off-free mindset.

And, of course, the communication companies.

There are distance limits to underground AC Transmission, the higher the voltage, the shorter the distance. That's why undersea cables are all DC

Excellent example of misplaced priorities. Chino Hills does not have wildfire-prone forests like the area surrounding Paradise, California.. Based on my experience as a CPUC intervenor, I believe the CPUC is extremely corrupt.