The Island of California

The high gasoline price rabbit hole is here, let's jump in!

I. The Island

I want you to know, Sancho, that the famous Amadís de Gaula was one of the greatest knights-errant. No, I’m wrong in saying ‘one of,’ he was the only one, the best, he was unique, and in his time the lord of all those in the world… He was the guiding light, the star of all brave and enamoured knights, and all of us who fight under the banner of love and chivalry should imitate him… I want to imitate Amadís …

Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes.

Castillian author Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo (1450-1505) followed the literary fad of chivalric romances which were all the rage in noble Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal) at the time. These were somewhat of a reginal spin-off of what literature dorks call the Matter of Britain which were literary works from Britain and Brittany well known for King Arthur.

Rodríguez de Montalvo compiled and amended three volumes of a work which would be published as Amadís de Gaula in 1508 which tells the tale of abandoned son Amadís of two star-crossed lovers; Perión, King of Guala (a fictional kingdom) and Elisena of (very real) England. Throughout the three books, Amadís, holding up somewhat to stereotypical medieval literature fell in love, rescued damsels in distress, became a hero, fought wizards, etc., etc. This all occurs via what could be aptly described as a serious of Medieval-type quests although still a far cry from modern Disneyfied takes. Amadís de Gaula was further made famous nearly 100 years later by Miguel de Cervantes when he wrote Don Quixote, often credited as the first novel. But we’re not here to joust at windmills for Rodríguez de Montalvo went on to complete a fourth work, mostly of his own accord, called Las Sergas de Esplandián (The Adventures of Esplandián) in 1510. In this work he tells the story of the oldest son of Amadís and the place his story takes place is a mythical island west of the Indes.

Know, then, that, on the right hand of the Indies, there is an island called California, very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise, and it was peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they lived in the fashion of Amazons. They were of strong and hardy bodies, of ardent courage and great force. Their island was the strongest in all the world, with its steep cliffs and rocky shores. Their arms were all of gold, and so was the harness of the wild beasts which they tamed and rode. For, in the whole island, there was no metal but gold.

–Las Sergas de Esplandián

The origin of the word California goes back even further - reported to be an Arabic loanword (the Moors occupied Iberia for over 700 years contributing hundreds of loanwords to languages which would later evolve to be modern Spanish and Portuguese) likely from Khalifa which roughly translates to successor or ruler.

Spanish Conquistadors, when visiting what’s now known as the west coast of the North American continent stumbled onto what they believed was a large island which today comprises of both much of the US state of California and the Baja California peninsula in modern Mexico. Historians believe these same Conquistadors were versed in Rodríguez de Montalvo’s last work thus being the reason the so-called island was named Cali Fornia.

The first revelation that California wasn’t really an island didn’t occur until 1701 when a Jesuit missionary suggested such but others remained skeptical of his claims. Several other Jesuit missionaries over the years tried to make similar claims with little success. Finally in the expeditions led by Juan Bautista de Anza between 1774 and 1776 was it confirmed that California indeed wasn’t an island.

But California, at least what used to be known as Alta, or Upper California is somewhat of an island - an energy island. Especially then it comes to oil.

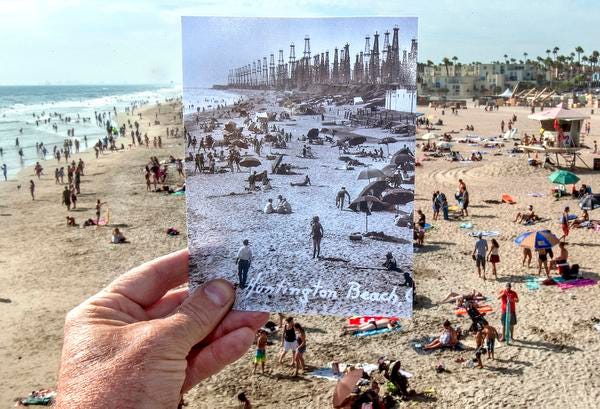

II. How/Where (Alta) CA Gets its Oil

California itself is actually a large producer of oil having notable production in Kern County, San Joaquin Valley and the Los Angeles basin. In the Los Angeles basin, it’s possible to “visit” several urban oil fields including ones in Signal Hill, Los Angeles, Fullerton, and Long Beach. The famous beaches of Newport and Huntington Beach were at one time littered with hundreds of oil derricks. There is even an oilfield under the city of Beverly Hills and said city up until a few years ago leased portions of their land for oil extraction using the money to fund local schools.

There is limited off shore production mostly off the coast of Santa Barbara. All new offshore production has been banned since a 1969 oil spill. There are portions of the state where so-called tight oil is located which could be extracted by hydraulic fracturing but the such process’ use is limited with an upcoming ban.

In general, CA’s “domestic” production composed of approximately 29% of the state’s oil consumption needs in 2021. Oil shipped from Alaska via ship comprised of approximately 15% in that same year. California’s in-state oil production and Alaska’s “exports” to the state have both been on the decline for decades. The remaining oil is all covered by imports from outside the United States.

Wait, let me repeat that: The remaining oil is all covered by imports from outside the United States.

But clearly any US-based reader here knows the states other than California and Alaska produce oil, right? Of course. Texas, North Dakota, New Mexico, and Oklahoma are some of the nation’s top producers. And the US produces so much oil that it’s now a net exporter.

But that remaining US oil is largely off limits to California.

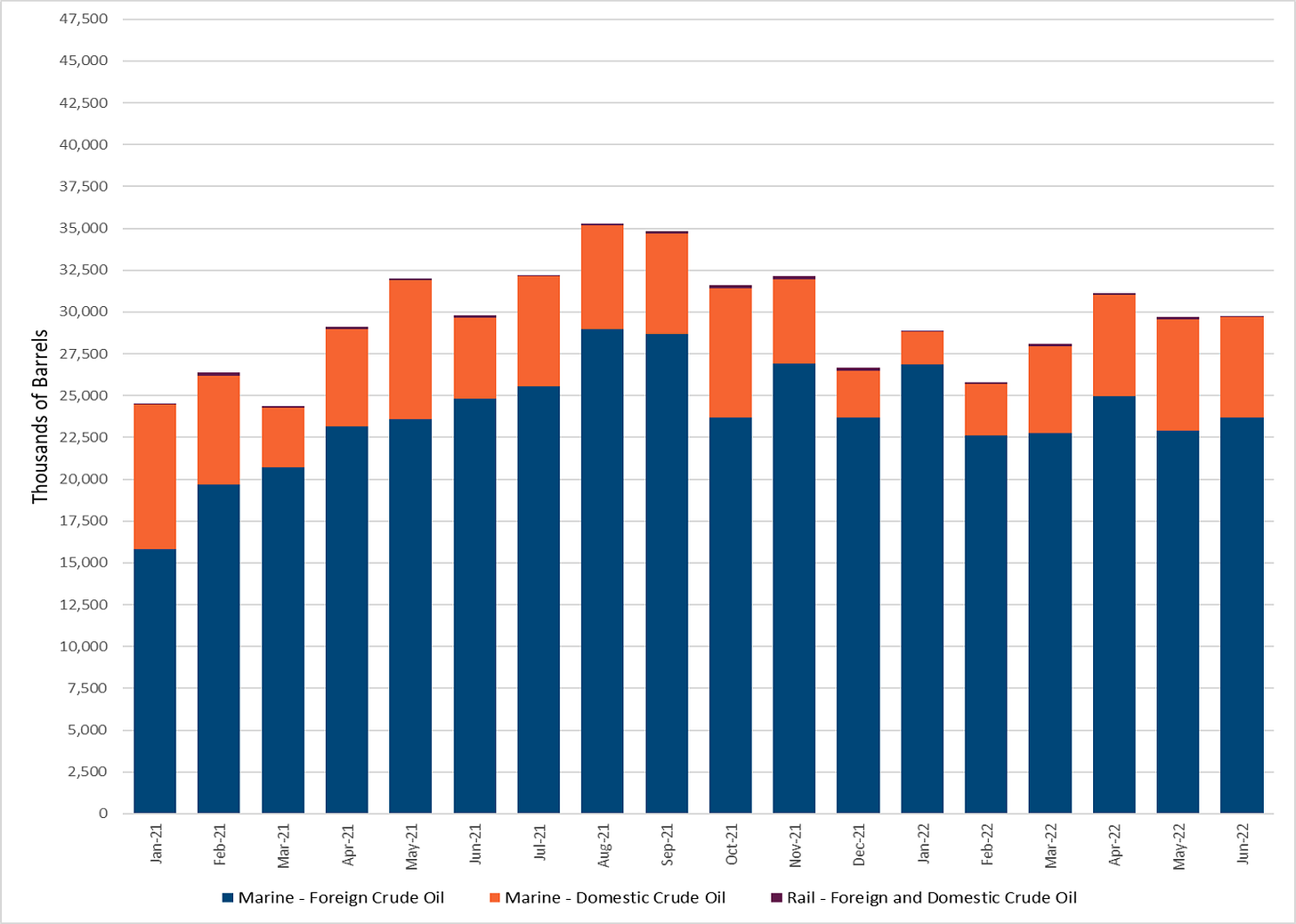

Oil is transported by ship, pipeline, rail, and sometimes truck. Rail and truck are negligible for CA imports so the rest is either by pipeline or ship.

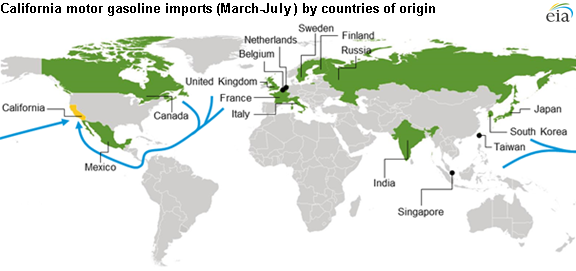

Well, no, scratch that too. Notice pipeline is also missing from that chart?

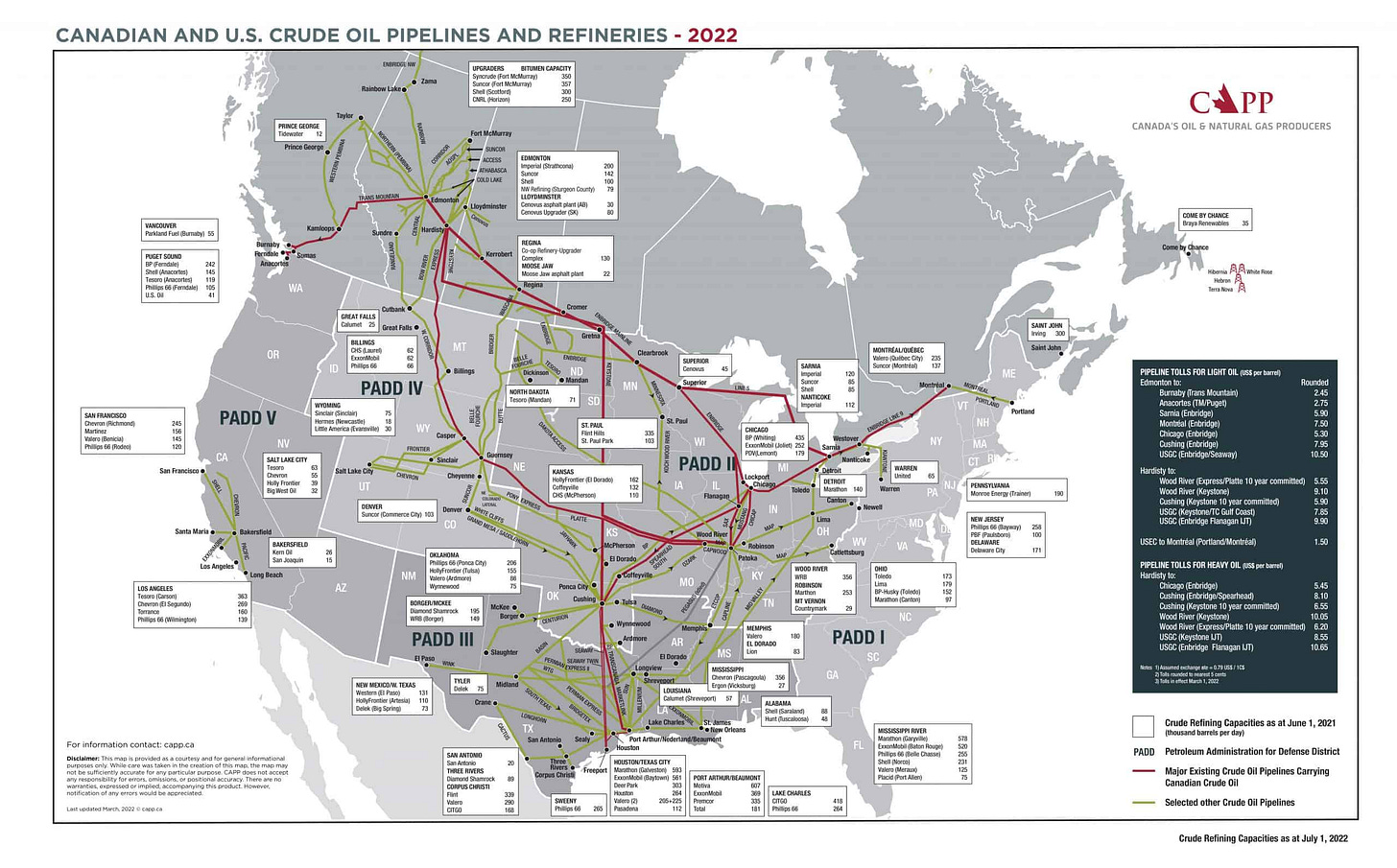

Taking a gander at the Canadian and US oil pipeline and refinery map below shows exactly what I mean when I say California is an energy island. (Click on image to enlarge)

Oil could theoretically be shipped via marine ships from other US states but this would most likely mean needing to come from the Gulf Coast. Any ship used between two US ports must be US-based (due to the Jones Act1) and would have to pass through the Panama Canal. There aren't exactly a lot of oil tankers with US flags and crews around.

Oil tankers aren’t exactly known for their green environmental impact either. Like most other large ships, they burn heavy fuel oil which is notoriously dirty. Tanker spills have caused the largest oil spills in history and when in port, they often burn the same heavy fuel oil in their engines to keep system power enabled which contributes to noxious air pollution in whichever port they are anchored.

In California this often means the heavily urbanized areas of Long Beach, Los Angeles, or the Bay Area where environmentalists correctly point out the disproportionate impact on local residents’ health and wellbeing. It’s time consuming to load and unload the tankers too. Pipelines work virtually 24/7 and have a far better safety record than train, truck, and in some cases, tankers.

Non-US Oil brought by tankers consisted of 56% of CA’s 2021 imports.

17.7% Ecuador

16.4% Saudi

15.8% Iraq

8.0% Brazil

8.0% Guyana

6.4 % Colombia

6% Russia

4% Mexico

3% Brunei

Non-US oil comes from a number of countries with a mixture of notorious labor and human rights issues and often far more lax environmental regulations than what is seen here in the US. Californians would be appalled to learn that Ecuadorian oil for example is sourced from destroying parts of the Amazon rainforest where several Indigenous Tribes have been displaced. Saudi Arabia and Iraq aren’t exactly shining examples of locations where human rights, especially women’s rights, are well respected either yet our leaders at the national level continue to beg from their cartel, OPEC, while stifling domestic production. So keep that in mind the next time POTUS goes begging for OPEC to increase production. That six percent from Russia in the figures cited above obviously had to change to zero this year as a result of sanctions against Russia for their invasion of Ukraine. Even a slight change in the import figures can make a difference in the state’s oil supply which can raise the price.

While the idea of producing more in-state oil in California is politically unpopular along the disconnected-from-reality upper middle class and elites along the coast who typically have zero clue just how dependent they are on petroleum, it’s far less controversial in places such as Kern County where it’s not only a provider of steady, high paying jobs, but also a cash cow for local governments.

Even the more urbanized counties such as Orange, Los Angeles, Ventura, and Santa Barbara would all think twice if these tax revenues disappeared overnight. Bureaucrats and environmental activists wax poetic about a so-called “just transition” for ending fossil fuels in general but don’t have the receipts to show their solutions can provide a viable replacement for these jobs. A similar parallel happened with the shutdown of nuclear plants which are often replaced by natural gas or renewable facilities. Nuclear plants typically have upwards several hundred to even one thousand highly skilled employees. Their replacements number in the dozens to low hundreds.

California produces very little in-state natural gas and the state lacks liquified natural gas (LNG) marine terminals too. As a result, roughly 90 percent of the natural gas used in the state is imported. The state primarily uses natural gas for generating electricity (45%) (as long time readers probably understand now, it saves the grid more often than not from supply collapse) followed by residential use (29%) , commercial use (9%), and industrial use (25%). Nearly all this natural gas is supplied by a handful of interstate pipelines providing just-in-time delivery (Second “leg” of the Fatal Trifecta) so the situation isn’t quite the same as petroleum (although pipelines are a major security risk) but nevertheless an issue to rely so heavily on imports as is typical with resource-poor islands. Recall the state and several cities are trying to decrease and/or eliminate the use of natural gas, presumably not knowing it’s an incredibly vital fuel and energy source that’s difficult and often impossible to replace. If their fantasies happened to be successful though (spoiler alert: they won’t), a part of the energy island metaphor would become moot.

California also remains an importer of electricity from neighboring states which also accounts for the lack of sufficient in-state electricity generation during periods of high demand such as last month’s heat wave. This is also most notably the third part of The Fatal Trifecta.

The energy island effect also has ties to diesel which I may cover in a different post. While diesel is important, its price increase isn’t as notable as gasoline immediately to the average consumer. The energy island effect is there though, especially with the increasing use of renewable diesel.

For the rest of the piece, we’re going to focus primarily on gasoline as it’s in the news now and will probably not be going away for some time.

III. So, Why Are Gas Prices So Volatile Expensive?

It’s complicated.

Well at least far more complicated than the narratives pushed by politicians and the Corporate Press. But it’s not too complicated that the average person can understand.

But first I want to explain how gasoline is made.

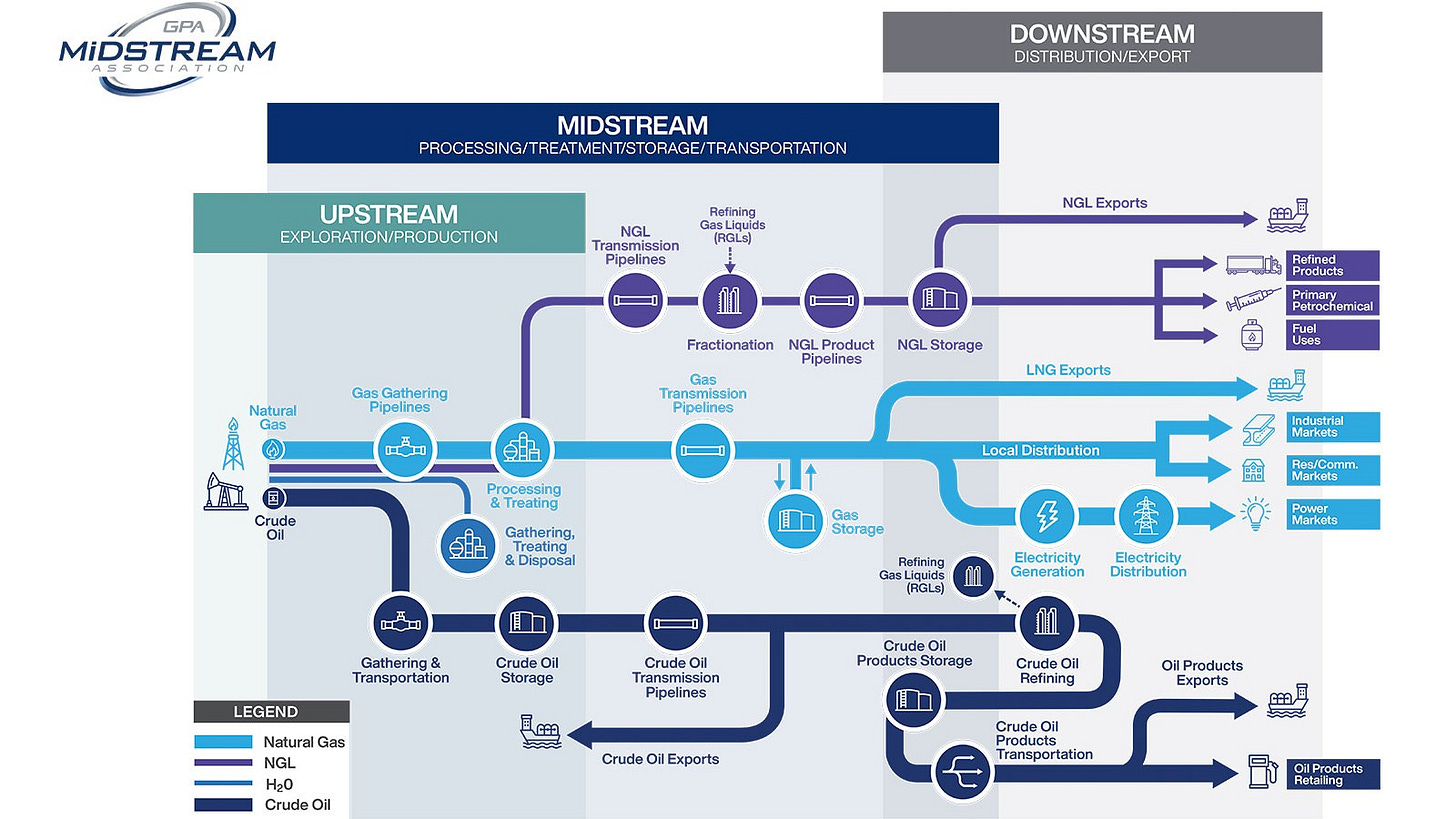

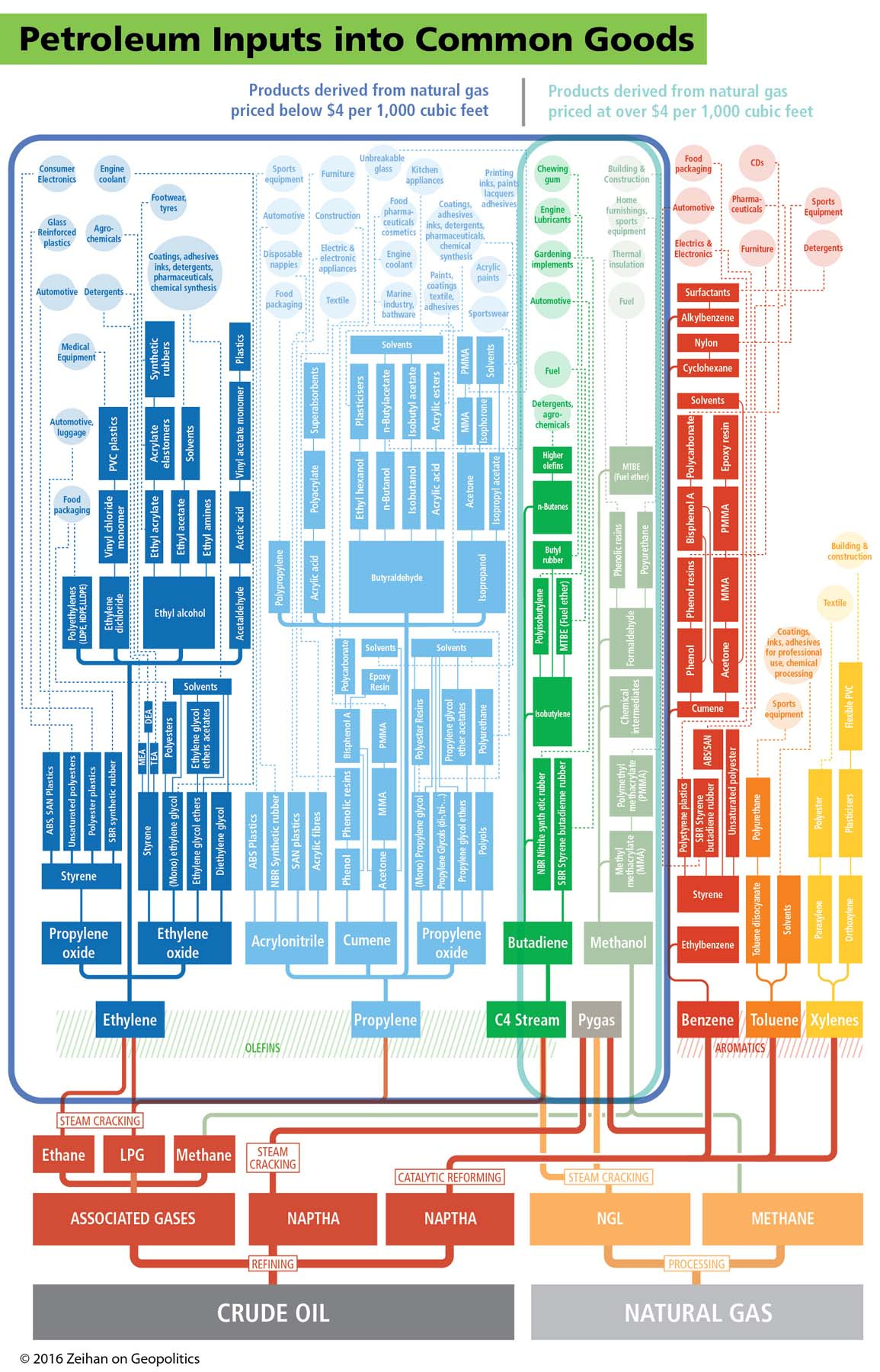

Everything explained so far is essentially the process in the entire oil well to pipeline is described by industry dorks as the upstream stage. Upstream starts at the oil well or rig and ends more or less once it arrives at a refinery. In order to turn that sweet (or sour) crude oil into gasoline and the variety of other petroleum-derived products, the oil must be processed in a refinery, which is part of the midstream stage, and finally there downstream stage which covers the distribution of the semi-finished or finished product, where it’s often further processed with additives (which for example give gasoline different octane ratings). In the case of gasoline, the fueling station where it’s sold to customers is the final node of the downstream stage and the entire supply chain.

If any component of any of these stages are upended or delayed, the final product’s price may swing drastically. Motor vehicle fuels such as gasoline and to a lesser extent diesel are products we consume on a regular bases therefore we’re often aware of even slight price swings.

Understanding this makes the “blame game” for why prices are so high that much more complicated. Keep this in mind when seeing flashy headlines and bombastic tweets about high gasoline prices. The petroleum supply chain is immensely complicated with multiple opportunities for something to go wrong. Often one problem causes another - domino effect galore.

Backing up to the midstream stage - gasoline, the fuel that runs most consumer motor vehicles is a processed product created by refining oil. The refining process is highly complicated and one can dedicate his or her entire career to just one part of the process without touching the others.

To simplify refining, lets use an example of a liquid mixture of water and alcohol. Both compounds have differing boiling points. When a mixture of the two are placed in to a still, heat is applied, both compounds boil - but at different temperatures. Water boils around 212 °F and ethanol alcohol around 173°F (at standard temperature and pressure yada yada). This is how liquors are made.

Crude oil is a complex mixture of various hydro-carbons (compounds consisting of both hydrogen and carbon) along with a lot of other trace materials such as sulfur. Crude oil is brought into a chamber called a distillation unit of which there are two types - atmospheric and vacuum - then heat is applied, and the various components making up the crude oil mixture are brought to boil at various temperatures.

In the case of producing gasoline for motor vehicles, this is done mostly using an atmospheric distillation unit. For our purposes, it’s really a complex liquor still.

Gasoline can also be produced in a fluid catalytic cracking unit which is a secondary process that takes place after distillation units. When produced by distillation, the product is called straight-run gasoline and when cracked, fluid catalytic cracker gasoline. Cracking to the layperson is nothing short of something between miracles and alchemy and is the source of countless substances modern society takes for granted.

But back to gasoline - the substance we’re looking for that is the predecessor to gasoline is distilled (or cracked using a separate process) at around 390 degrees and are called naphthas.

Naphthas are highly volatile, which means they evaporate quickly relative to other compounds such as - say motor oil- and they’re highly flammable. If you’ve ever spilled gasoline while at a filling station, you know it doesn’t stick around for long whereas an oil leak from your car stays around until it’s cleaned up. Volatility and flammability are both chemical properties that make gasoline an excellent fuel to use in internal combustion engines. But these two properties also have some downsides.

When gasoline evaporates into the atmosphere, not only is there an undesirable smell, and a well-known carcinogen is evaporating but it also can produce ozone. Ozone pollution causes respiratory issues in people, especially children and elderly and also contributes to smog production.

Gasoline which evaporates too quickly inside an automobile’s fuel tank is also an issue as eventually all the gasoline will evaporate out of the vehicle but can can also cause vapor lock which means the gasoline inside the tank evaporates within the tank before it reaches the fuel pump. Gasoline tends to evaporate that much more quickly and is thus more volatile in slightly higher temperatures such as during the summer or in warm climates in general.

At service stations in California, there is even a distinct type of pump to alleviate the small amounts of gasoline vapor that evaporate during the filling process. These are mocked by motorcyclists as pump foreskins.

Sorry, you if you can never unsee that again!

Their technical name are vapor recovery hoods.

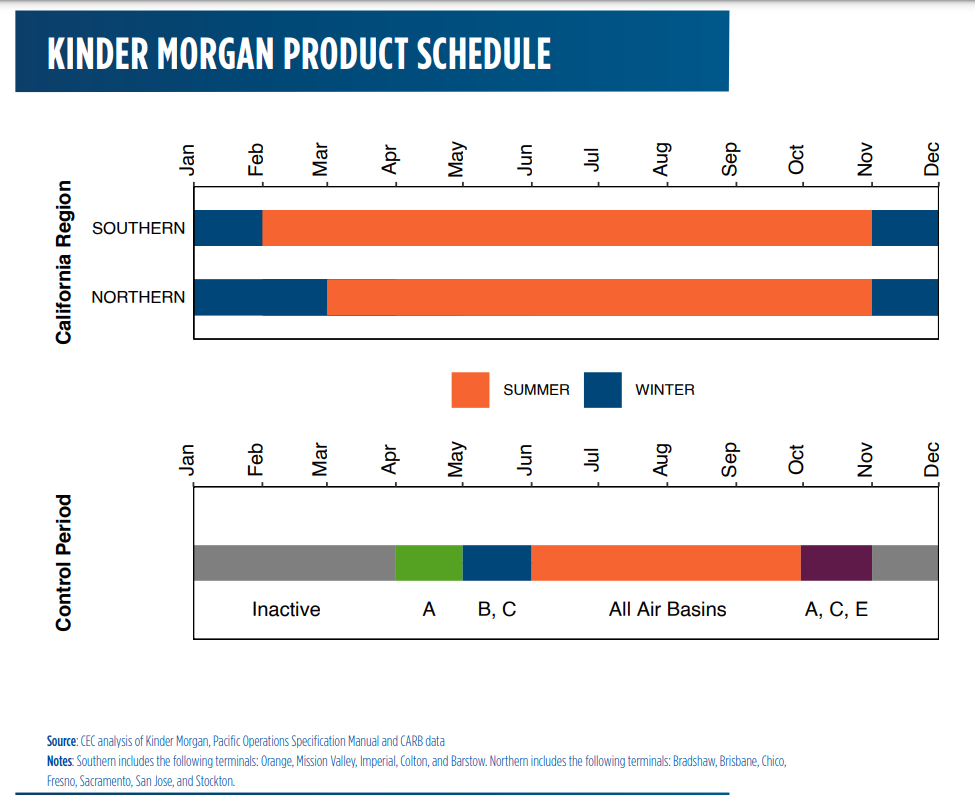

The volatility issue is in large part alleviated by switching between what are called summer and winter blends of gasoline. The idea is to formulate summer gasoline to decrease its volatility and to increase volatility for winter blends. In the latter, the lower temperatures in winter result in a less volatile gasoline which makes it more difficult to pump to and burn in the engine. In industry lingo, this is called the Reid Vapor Pressure (RVP). Both seasonal blends are looking for the “sweet spot” that optimizes for ideal combustion by an internal combustion engine while trying to minimize the nasty side effects listed above. Summer blend (low RVP) is more complicated for formulate (often uses the fluid catalytic crackers to produce some of the gasoline) and is thus more expensive to produce and that cost is passed down to the customer.

The Federal Government mandates summer blend gasoline be produced by refiners, terminals, and storage facilities between May 1st and September 15th and gas stations sell these fuels between June 1 to September 15th. California, of course, does things different and mandates a range of dates depending on the geographical area of the state.

This switchover also requires re-tooling or reconfiguring certain parts of refineries, which typically operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, and almost 365 days a year producing not just gasoline but diesel, other fuels, and a massive variety of products. This takes time and costs money - which is then passed down onto the consumer. The switchover also generates issues for the petroleum products pipelines (separate from crude oil pipelines, and a part of the downstream stage) and storage faculties (also downstream) which are the final place gasoline is stored before being delivered via a tanker truck to a fueling station.

To simplify things immensely - a products pipeline typically cannot have a mix of the two seasonal blends of fuels, nor can storage tanks otherwise this mix doesn’t comply with the regulated RVP values. Distributers attempt to stockpile the upcoming fuel in advance but it’s difficult to anticipate demand of the end customer.

Gasoline’s flammability has its downsides as well - under combustion it produces several undesirable chemicals as waste products. The previously mentioned ozone, followed by nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur, benzene, acetaldehyde, formaldehyde, and up until the mid 1980s - lead. (Lead is still permitted for use in aviation fuels.) These products cause air and water pollution along with respiratory and reproductive harm in humans and wildlife, and some such as sulfur mess with the catalytic converter on automobiles decreasing their ability to reduce hazardous tailpipe emissions. Refiners can do a number of things to reduce these hazards and are obligated to by the US Federal Government via the Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA really got the teeth to hammer down on these issues thanks to the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendment which in part mandates refiners produce gasoline products to target specific air quality issues. States are allowed to mandate their own gasoline products as they see fit provided they meet the requirements from the EPA. California, presumably to nobody’s surprise, has their own special requirements, regulated by the CA Air Resources Board otherwise known as CARB.

And here’s where we get back to the energy island.

The US Energy Information Administration - the federal busybody for tracking all things energy, divides the country up into Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts or PADDs which were established during WWII. California sits inside PADD Number 5 which also comprises of the other West Cost states plus Nevada, Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii. Alaska and Hawaii are special cases of their own (also energy islands, in the latter, that’s also literally true).

We turn to the EIA for a discussion on the nuances of PADD 5. Emphasis mine.

PADD 5 is relatively isolated from other U.S. markets and located far from international sources of supply, so the region is very dependent on in-region production to meet demand. Additionally, California's more-restrictive gasoline specifications (CARBOB) limit the availability of supply from other markets. Mainland PADD 5 has three distinct supply/demand centers (Figure 1) and is geographically separated from other markets by mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. As a result, moving product to southern California requires long lead times. - EIA

The figure differs from the one cited earlier in that it’s referring to product pipelines, not crude oil pipelines. Recall CA has no inter-state crude oil pipelines and instead either extracts oil from inside the state or gets it via ship from out of state. All of California’s adjacent states have some refining ability of their own but also they possess product pipelines that can provide finished gasoline (and other petroleum products) to them from other places. California only has product pipelines that export to adjacent states - most notably Nevada and Arizona and some of the state’s refineries actually produce non-CA gasoline for them.

Couple this with the fact that other states do not use California’s special blends of gasoline (CARBOB) so these are generally produced at in-state refineries. CARBOB, a type of reformulated gasoline has both summer and winter blends. CARBOB, much like summer blend, is more difficult and expensive for refiners to produce and CARBOB is one other reason why the cost of gasoline in the state is more than adjacent states. Other states or regions of other states also use the Federally-defined/mandated reformulated gasoline but it differs from California’s special reformulated gasoline, or CARBOB.

The price difference for consumers at the pump is reflected in the EIA’s retail gasoline price figures split by PADD region. California, being the largest population with highest gasoline demand alone raises the average across PADD 5 to the extent where EIA shows an additional prices for PADD 5 with CA removed. Notice the difference in price!

The price difference is also noted in the EIA’s figures for spot prices. Here they do differentiate between conventional gasoline sold across much of the US and California’s special reformulated gasoline, which they refer to as RBOB.

Notice the price difference!

Now it is possible for out of state refineries to produce CA’s special reformulated gasoline (CARBOB) but it’s often not economical for these refineries to temporarily scale down production to “re-tool.” It’s also more expensive to deliver finished product to CA due to its lack of import-capable product pipelines (recall the EIA Figure 1 above, note the direction of the arrows!) When other refineries do produce these products for the California market, their lead times are often long - taking up to several weeks to arrive at the pump. When this does happens, it’s possible that automobiles in California are running on gasoline refined to California standards from places as far away as Singapore!

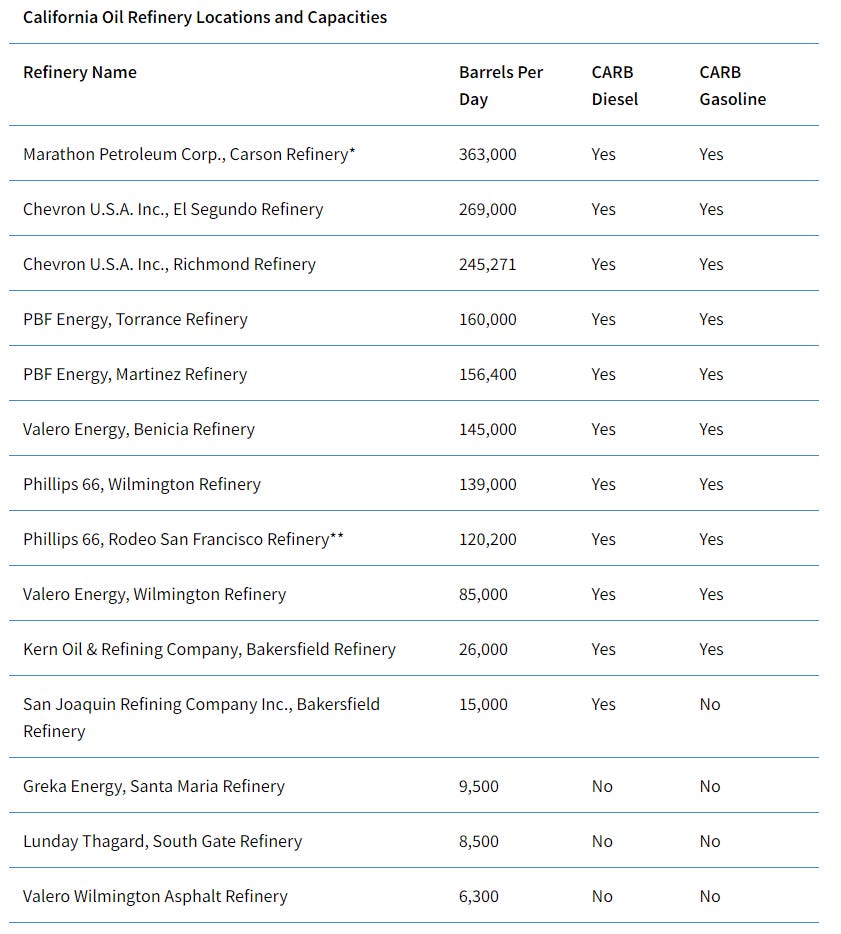

Due to these unique circumstances, most of the state’s special gasoline is refined in California’s own refineries. California has a total of 47 refineries or former refinery sites. Of those 47, only 13 are in operation and of those 13, ten produce CA-approved gasoline. The remaining refineries produce only asphalt. This limited number and isolation spells doom if/when one refinery is knocked offline, which does happen.

A 2015 refinery outage in the state highlights just how drastic price swings can be. Per an EIA article from the time, emphasis mine.

On February 18, an explosion and fire occurred at the ExxonMobil refinery in Torrance, California. The Torrance refinery, the third-largest refinery in southern California, has about 20% of the region's fluid catalytic cracking (FCC) capacity and is an important source of gasoline and distillate supply. ExxonMobil's website indicates that Torrance produces about 117,000 barrels per day (bbl/d) of gasoline (about 15-20% of southern California's supply). Based on publicly available information, it can be estimated that Torrance also produces about 50,000 bbl/d of distillate and jet fuel (about 10% of southern California supply).

California gasoline markets continue to adjust to the February 18 explosion and fire at the ExxonMobil refinery in Torrance, California, located southwest of Los Angeles. The ExxonMobil refinery is the third-largest refinery in Southern California. The refinery unit affected by the explosion, the fluid catalytic cracker (FCC), is essential to making gasoline. Torrance's FCC represents 22% of the region's total FCC capacity, making it a key source of gasoline and distillate fuels that meet California's very stringent fuel specifications. On September 30, ExxonMobil announced the sale of the refinery to PBF Energy, which will be PBF Energy's first refinery on the West Coast once the sale is complete.

Because of its unique product specifications and long distance from international gasoline markets, California specifically, and the West Coast in general, does not typically import much gasoline. As a result, the sudden loss of supply from the Torrance refinery resulted in immediate supply shortfalls and higher wholesale and retail prices. The higher wholesale prices covered the costs of importing more gasoline from distant markets into California to make up for the supply shortfalls.

There are other in-state refineries not listed that are currently idle and are being converted for renewable diesel production which differs from petroleum-based diesel. Refineries across the country are being converted to produce only renewable diesel which reduces the capacity to produce gasoline and other petroleum products overall across the nation. Both in-state and national refining capacity has thus been reduced which is also in part an explanation as to why gasoline prices have been so high in 2022 across the country. Politicians, bureaucrats, and the corporate press have neglected to include this important detail in their #PutinsPriceHIke and #greedyoilcompany narratives though!

More on renewable diesel in Doomberg must read piece on the subject.

As for building new refineries and/or retrofitting them to produce more petroleum-based products, it is nearly impossible both inside the state and across the rest of the country to do so. Governments will not allow for the permitting, the financing is next to impossible to obtain thanks to the ESG movement, and the politicians make an effort to clamp down and behave in a hostile manor to the petroleum industry.

Interlude: Quick Recap

California’s crude oil relies on in-state extraction and importation mostly via tankers from Alaska and foreign countries. The state lack interstate crude oil pipelines to transport crude from the lower 48 or Canada.

The state has special formulations of gasoline and uses summer blends for a longer period of the year than do other parts of the country. Both are more costly to produce than conventional gasoline or winter blend.

These special formulations of gasoline are generally produced only in the state’s refineries. Out of state refineries can also process the products, at greater expense and with longer lead time.

In-state refineries risk breakdowns, flat out closure, or conversion to renewable diesel faculties. All three decrease the state’s total capacity to refine special CA gasoline which raises prices for consumers.

IV: The Taxes

What a customer pays for a gallon of gasoline depends on the price of crude oil (traded on international markets), refining costs, and distribution and marketing costs. At each step of the process, each party charges a slight profit, which provides an incentive for them to keep producing and for reinvestment in their workers and/or assets. The same politicians, bureaucrats, and corporate press (Clown Triad) who blabber about oil companies (who are only part of this entire above-mentioned supply chain) “price gouging” tend to also assign a negative connotation to profits2.

Needless to say, another part of the cost for a gallon of gasoline prices are the taxes to local, state, and the Federal government.

A recent KBS article elaborates:

Paying more than $6 per gallon for gas has become a normal situation throughout San Diego recently. On Friday, that number creeped a little higher as California’s gas tax went up by 5.6%.

That takes the current tax up to 53.9 cents per gallon.

- “California’s gas tax increase raises already sky-high prices” KBS News, 7/1/22

Except it’s not quite correct.

That 53.9 cents per gallon is just the state’s excise tax which is the highest in the nation.

That does not include the Federal gas tax of 18 cents per gallon nor the sales taxes charged by local governments, the state’s 2 cent per gallon underground storage fee, and two seldom mentioned other taxes fees; the CA Cap and Trade (C&T) Fuels Under the Cap (FUC) fee, and the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) fee.

There’s a slight semantic difference between tax and fee, leaving the latter to be excluded more often than not, but they are effectively a tax on the price of the gasoline. Let’s get real!

The C&T FUC, added in 2015, varies depending on the price of cap and trade allowances but is currently around 14.5 cents per gallon. The LCFS was added in 2011, its price fluctuates based on the price of LCFS credits, which petroleum product suppliers are required to purchase from producers of so-called green fuels such as ethanol, biodiesel, renewable diesel, and renewable natural gas. Renewable electricity providers can also sell these credits. The current fee is 22.6 cents per gallon.

When all’s set and done the taxes (or taxes and fees if we’re to be precise) on one gallon of gasoline in California at almost $1.20 per gallon.

Both the C&T FUC and LCFS are strangely left out of the CA Energy Commission’s weekly published Estimate Price Breakdown and Margins tables.

These taxes and fees aren’t the cause of extreme price fluctuations but they do explain in part why the state’s gasoline prices in general are more than the rest of the US.

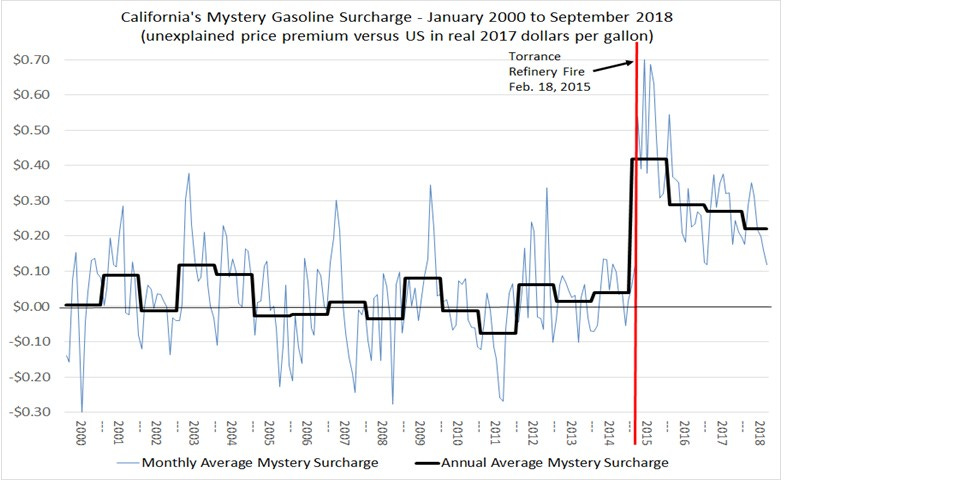

V: The Mystery Gasoline Surcharge

Recalling the 2015 refinery fire mentioned in Section III which temporarily knocked offline a large part of the state’s refining capacity resulting in an large jump in gasoline prices, some folks noted that after the refinery fire was extinguished and the facilities brought back online, that the prices didn’t drop all the way back to their previous levels. This has been coined, the “Mystery Gasoline Surcharge,” by Berkeley Professor Severin Borenstein who has been blogging about the phenomenon for several years. He describes the MGS as the following in a May 2019 :

[The] MGS is the difference between California’s gas price and the average price in the rest of the country after you take out the state’s higher taxes and environmental fees, as well as the cost of making our cleaner-burning gasoline. The MGS is a mystery, because prior to a refinery explosion in February 2015 it pretty much didn’t exist. It averaged about two cents per gallon from 2000 to 2014, but since then it has been adding more than 25 cents to the price of California gasoline. - source

Visually he shows the MGS in this chart showing the phenomenon before and after the 2015 refinery fire.

While Borenstein may be onto something, nowhere in his analysis can I find anything related to the several refinery closures and/or conversions to bio-fuel only plants within recent years in the state, let alone a similar decline nationally in refining capacity. Nevertheless the MGS it’s an interesting hypothesis which if Borenstein is correct, pins some of the blame for higher gas prices directly on the refiners which would be a politician’s dream if true.

VI: Closing

The Spanish conquistadors got it wrong believing California was an actual island. That myth perpetuated for decades. Today, California is home to almost 40 million people and is often touted as being the fifth or sixth largest economy in the world if it were considered a sovereign nation. New myth(s) perpetuate. Modern Californians understand California isn’t physically an island but don’t necessarily grasp that it is metaphorically one when it comes to energy. The politicians and bureaucrats who control the state desire to phase out gasoline and diesel powered vehicles in favor of all-electric vehicles. They’re also interested in eliminating the use of all other fossil fuels and while they presumably don’t realize this yet - hundreds of other industrial processes, and products rely on fossil fuels - especially petroleum. This too is a myth - a dangerous one at that.

Puerto Rico suffers from a similar Jones Act-imposed issue after recovering from Hurricane Maria in 2017 and now from Hurricane Fiona. Puerto Rico instead must import oil from Trinidad and Tobago as opposed to receiving domestic oil from the mainland United States. Both President Trump and Biden issued temporary exemptions to the Jones Act after both hurricanes but it still doesn’t fix the long-term problem.

We don’t want to get into elementary economics here, but these takes by these parties are incredibly unserious and further prove how unqualified each of them are to contribute to this important discussion. Not understanding energy and economics is deadly - especially when it’s people with power and influence, and that’s largely the thesis of this entire Substack. If you’re not a member of the Clown Triad, and have been mislead by their narrative please please please pickup a copy of Economics in One Lesson (notes) , How to Think about the Economy: A Primer or any of Saifadean Ammous’ works. Simply skimming ANY one of these books will make you smarter in economics than 99% of politicians, bureaucrats, journalists, and sadly even many economics majors or professors.

Brilliant article and it should be required reading (with exams at the end) for all politicians, eco-warriors, etc. before they are allowed to opine on the subject in any way. As a life long participant in the oil and gas business, I simply cannot understand how those in power or those aspiring thereto have allowed themselves to be distracted from the fundamentals of the industry that supports modern life worldwide

Just learned of this stack. Well written compressive piece.

As for the mystery extra margin I have a hard time believing the professor is serious.

The refining margins are easy to see and they ebb and flow, the reduced number of players in the production of California spec fuels is obvious, but so are the significant and pervasive rules and regulations to opening/running fuel service stations.

From infrastructure and personnel regulations to local jurisdictions making it harder to operate. This leaves those with locations in similar positions with captive consumers. After the explosion the operators all recognized they could charge more lose some marginal amount of sales volume yet make significantly more money. Politicians can’t attack the “little guy “ , but the professor surely can research the obvious.

The lack of street competition has created a market where those operating can command much higher margins. Plus if, for example, someone is operating a site in Santa Monica the real estate cost, taxes and insurance are going to force them to charge a higher margin to make the business successful.

Average street margins have widened massively since 2015. Driving hordes of consumers looking for lower priced fuel, So much so that Costco has become the largest reseller of fuel while making upwards of 10x what they previously made, the loss-leading product has become a boon to their overall bottom line—mainly from California operations.

I’m not angry at the station operators. I’m upset at the bureaucrats that think there’s some realm of possibility Californians can walk, bike or take public transportation to the extent the bureaucrats fantasize about. The public service class are all trained in central planning and by definition competition is harmful, when it’s absolutely essential to forcing prices down.

Rather than tax the business man out of business they should deregulate the business man out of business, and in this creative destruction process help the consumer especially those in the lowest economic rungs just trying to live a purpose filled and simple life!