El Sueldo de Chile y el Futuro Pa' la(s) Transición(es)

"The Salary of Chile and the Future of the Transition(s)"

This is a very long piece, and it’s probably not the best quality writing but please bear with me as the only way to improve is to keep writing. My intent here is to give a background on the past 60 years of Chile, which I once called a home temporarily, and connect it to this Sunday’s (4 September) upcoming Constitutional Plebiscite along with the usual energy-related content covered here. It’s difficult to find a single source for the Chile background, especially in English. So, enjoy.

I. La Poderosa

Fuser as his friends often called him was a medical student in his early 20’s from an aristocratic Argentine family who grew up heavily influenced by the numerous philosophy and political books of all flavors that lined the bookshelves of their home. Fuser liked to travel, as the cliché often goes, “off the beaten path,” by avoiding tourist areas, hitchhiking, and knocking on the doors of strangers home asking for a place to sleep. He’d been an experienced traveler around the region among many trips having traveled solo on a 2800 mi trip through Northwestern Argentina on a motorized bicycle. Not having been satisfied with these travels, he and a fellow friend Alberto took off on a 1939 500cc single cylinder Norton motorcycle which they nicknamed La Poderosa. Their goal was to travel the entire length of South America, including a hop to Miami, and then return to Buenos Aires.

Fuser and Alberto trampled across Argentina having wrecked the overloaded bike several times, accidentally killing a dog thinking it was a predator, and Fuser experiencing a breakup with his girlfriend via letter which solidified his disconnection from his old life in Argentina. They also ran out of money at this stage and relied on begging and exchanging their labor for food and places to stay. Both used their skills from medical school made to treat people they met along the way. He also began to be increasingly frustrated and saddened at the poverty he’d see.

They eventually made it into Chile, which at the time was far more poor than Argentina, and eventually had to ditch the motorcycle as it became increasingly unreliable and eventually impossible to repair. They instead resorted to hitchhiking and even boarded as stowaways on a ship but eventually ended up in the copper mining town of Chuquicamata (Chuqui) in the Atacama Desert of Northern Chile. There, Fuser noted the poor treatment of the Chilean mining workers by the mine’s owners, the Butte Montana based Anaconda Copper Company , as well as the nature of the mining itself which was extremely hazardous resulting in numerous injuries and deaths of the miners.

Fuser and Alberto continued their trip North into Peru making it to a leper colony deep in the Amazon where Fuser grew ever more frustrated at how those inside the colony were being treated. They further made it to Colombia and split ways in Venezuela with Fuser flying to Miami and then back home to Argentina1. Fuser did return to Argentina to graduate from medical school and he made other trips throughout Latin America but he became far more interested in “activism” as he became further disillusioned with treating individual patients and more interested on “treating” what he believed were the root causes of many of the injustices he saw throughout Latin America. Fuser became so entrenched in his perception of social justice and later full-blown Communism he went to a few other Latin American countries including one particular infamous Caribbean island’s revolution and even became a famous on t-shirts.

In case you don’t recognize him, here’s a better image2.

II. A Turbulent Past

Chuqui still exists today, in fact it’s one of the largest open pit mines in the world. Anaconda also owned a large copper mine called El Salvador. A second American mining company, Kennecott Copper Corporation, owned and operated El Teniente, which is the deepest underground copper mine in the world to this day. These mines are just a handful of Chile’s total production.

In the 1950s, when Che and Alberto visited, these three mines in particular were called La Gran Mineria , or roughly translated as The Great Mines. La Gran Mineria in the mid 1950s were seen as a problem in Chile for they were owned and operated by foreign companies. They were accused of poor labor practices and for exporting the mineral wealth without proper compensation to the country’s citizens aside from well connected politicians and elites. For anybody with even a low-level understanding of Latin American politics, this is a story that’s repeated itself across the region time and time again.

Che noted in his memoir, The Motorcycle Diaries, where all the above was also recounted, that at the time they visited in the early 1950s, Chile produced a whopping 20 percent of the world’s copper. He insisted it was primarily used for “weapons of destruction3” He also commented on the political scene in Chile noting an upcoming presidential election where he expected former dictator Ibáñez del Campo was expected to win against three other candidates; Pedro Enrique Alfonso, Arturo Matte Larraín, and Salvador Allende-Gossens. Allende was unable to sustain a significant amount of votes due to a 1940’s law passed during the administration of Gabriel González Videla ironically titled Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia (Law of Permanent Defense of Democracy) which banned Communist and other leftists4 from voting.

Che notes in The Motorcycle Diaries as the following:

It’s likely that Ibáñez will observe a politics of Latin Americanism, manipulating hatred for the United States to gain popularity; nationalizing the copper mines and others (although the fact that the United States owns huge Peruvian mineral deposits and is practically ready to begin exploiting them doesn’t greatly increase my confidence that nationalization of these Chilean mines will be feasible, at least in the short term); continue nationalizing the railroads and substantially enlarge Argentine–Chilean trade.

Chile as a nation offers economic promise to any person disposed to work for it, so long as they don’t belong to the proletariat: that is, anyone who has a certain dose of education and technical knowledge. The land has the capacity to sustain enough livestock (especially sheep) and cereals to provide for its population. There are the necessary mineral resources to transform it into a powerful industrial country: iron, copper, coal, tin, gold, silver, manganese and nitrates. The biggest effort Chile should make is to shake its uncomfortable Yankee friend from its back, a task that for the moment at least is Herculean, given the quantity of dollars the United States has invested and the ease with which it flexes its economic muscle whenever its interests appear threatened.

Ibáñez del Campo won the 1952 election as predicted and began the process of nationalizing the country’s copper industry by creating both the Ministerio de Minas (Ministry of Mines) and Departamento del Cobre (Department of Copper). For those stuck in the typical Left-Right dichotomy, especially for readers in the USA, del Campo’s political affiliations break apart this mental prison quite well for he was of the Center-Right party at the time yet had support of the Popular Socialist Party and even feminist María de la Cruz (first Chilean woman senator) who also served as his campaign manager. Ibáñez del Campo also repealed the Ley de Defensa Permanente de la Democracia prompting the return of Neruda which also amplified the Chilean left by allowing their members the right to participate in politics again.

Other than the creation of those two government bodies, the nationalization process sat mostly on the back burner until the late 1960s and two presidents later. Eduardo Frei Montalva signed agreements with the foreign copper firms buying out as much as 51% of their interests in Chile and ordered the companies to send more of their profits to the government. This "negotiated nationalization,” was intended to not upset the foreign interests or their home nations’ governments. Over the next several years, the Chilean government would be permitted to slowly acquire the remaining portions of these corporations. Of course in the typical leftist fashion, this process wasn’t “good enough,” “fast enough,” and was alleged to be catering to the “American Imperialists,” since the Chilean people still did not have control over their greatest source of wealth, which at the time composed of nearly 80% of their entire exports.

But copper nationalization was kicked into overdrive after the election of Salvador Allende in 1970 who is recognized by many as the first democratically elected Socialist Marxist head of state5.

One thing Allende and most of his political opponents in the 1970 election mutually supported was a more rapid copper nationalization process as opposed to “negotiated nationalization.” Congress passed his proposal unanimously and the law came into effect on a day known in Chile as Día de la Dignidad Nacional (National Day of Dignity) which is still celebrated today by many inside Chile. Immediately, the remaining foreign copper assets were seized and the compensations stopped.

But copper nationalization was only a part of his "La vía chilena al socialismo" ("The Chilean Way to Socialism") programs which also included nationalizing the coal industry, healthcare, and telecom. Between the copper nationalization and telecom nationalization, the US Government and other interests grew increasingly furious. (Later it was revealed the US tried over the years prior to Allende’s election to sway Chilean politics in their favor). Once Allende began to get cozy with Fidel Castro (long after Che left Cuba) and the USSR, who didn’t aid Chile as much as he hoped, the US became even more upset. This was also the middle of the Cold War. Nixon even once described Latin America as a “Red sandwich” with Cuba on one end and Chile on the other with the rest of Latin America in between. But Allende was also becoming increasingly unpopular inside Chile. His programs, along with the mingling from the US led to labor and trucking strikes, supply shortages, and hyperinflation.

In the summer of 1973 Chile saw three major events; a failed coup called “Tanquetazo” led by disgruntled military members, a constitutional crisis questioning the legitimacy of Allende’s government, and finally the 11 September Coup. The 11 September Coup installed a military junta eventually led by Augusto Pinochet.

The Junta and Augusto Pinochet are well-known their brutal human rights violations6 that occurred, the 1980 Constitution, and the free-market oriented reforms otherwise known as the “Miracle of Chile.”

The 1980 Constitution, still in effect today although heavily modified over the years, was approved by roughly 2/3 of the voters albeit in a mandatory plebiscite in the middle of a regime which crimped down heavily on basic human rights. It however contained a number of “transitional” clauses which were intended on ratcheting back the Junta and returned Chile to a democracy (with restrictions such as Pinochet being appointed to a lifetime position in the Senate). This transition ultimately began in 1988 when another plebiscite was held asking voters whether to keep Pinochet for another eight years or begin the transition to democracy by allowing voters to vote for someone else in a future election. In 1990, Congress was restored in part due to an election held by the voters and since then Chile has been labeled as a modern democracy.

The market reforms (started) under Pinochet influenced by Milton Freidman and a group of University of Chicago trained economists known as “The Chicago Boys” who are credited with much of Chile’s jump from one of the poorest countries in Latin America to one of the wealthiest. (I could write a whole piece on just this but for the sake of time, defer to Axel Kaiser’s, The Fall of Chile.) These reforms which continued well after the Pinochet regime consisted of deregulation and privatization but didn’t completely privatize the country’s copper industry. Instead it kept La Gran Mineria in ownership by the state-owned copper mining company, CODELCO but allowed others to open new mines.

III. Ratcheting Up

Chile’s successes have not been universally accepted. Groups on the left especially, both inside the country and outside regularly repeat that income inequality in Chile remains large, the private pension system is insufficient, the private water system is problematic, the school voucher system isn’t working, and of course the legacy of Pinochet remains - especially with the 1980 Constitution still in effect. The left too as an entire movement, much like in other places, wants guaranteed (positive) rights for nearly everything and for anybody under the sun and greater expansion of government as a provider of social services and protections. To be fair, I’m painting a broad brush here but do acknowledge many on that side of the spectrum DO see a lot of things others do not see.

The divide in Chile has never really gone away - in fact it’s gotten worse in many ways. The Left-Right divide aside, the memories of Pinochet’s human rights violations remain in the memory of many Chileans and there are plenty of Chileans who defend Pinochet insisting that his regime did more good than harm for Chile. For Americans who think the Trump ordeal is bad, Chile would ask you to hold an Escudo.

Part of this divide became front and center thanks to Chile’s fierce student movement largely led by the Universidad de Chile’s Student Federation (“la FECH”) and the election for their leader in 2011. Interestingly enough, this election garnered coverage from international Corporate Press outlets such as the New York Times, who (unsurprisingly) were rooting for “the most glamourous Revolutionary” Camila Vallejo, a member of the Communist Party. Instead though, a law student by the name of Gabriel Boric won the position.

At the same time largest student-led protests in recent history rattled the city of Santiago with a large list of demands - typical of student protests and especially in Latin America. Boric and Vallejo both were elected into the Chilean Congress a few years later while Michelle Bachelet, who previously served as President from 2006 to 2010, won a second term. Additional protests whose participants numbered at over 100,000 demanded Bachelet impose measures to swing Chile harder to the left.

Unrest later exploded again in late 2019 during the second term of right wing President Sebastian Piñera. What started as a protest against Santiago Metro fare hikes became the largest protests soon to be riots in Chile, and probably in all of Latin America. “Chile Woke Up” described the New York Times who attributed the protests to the inequalities resulting from the Pinochet dictatorship. The protests later swelled across the country resulting in millions of dollars in damages, a declaration of a state of emergency by the government including curfews, and the deployment of the Chilean Army. Dozens of people died, thousands injured, and thousands more arrested. Along the long list of demands was once again - a new Constitution. Piñera agreed met with prominent foes including Boric and Vallejo and agreed to hold a referendum asking voters if they wanted a new Constitution. Shortly after the Chilean Congress approved the measure.

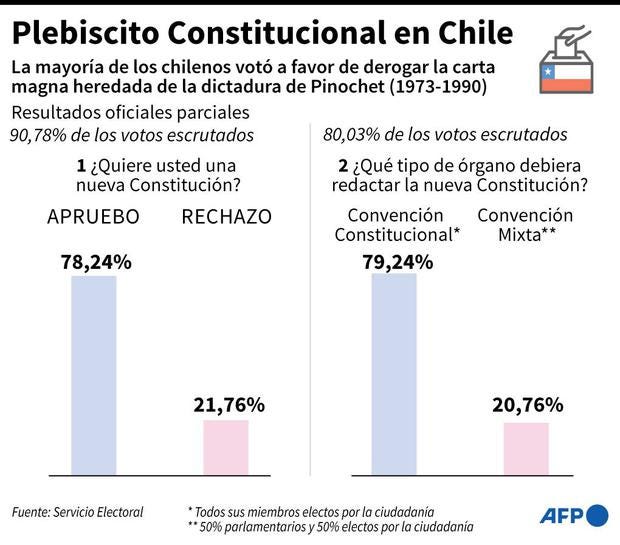

The actual plebiscite occurred nearly a year later, delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and it asked two simple questions: should the country adopt a new constitution (yes or no), and if yes, should the proposed constitution be drafted by a Constitutional Convention of members directly elected to fulfil the task or with a “mix” of parliament members and citizens; 78% of the voters (51% voter turnout) decided on “yes” for a new Constitution nearly the same for “yes” for a Constitutional Convention.

The Constitutional Convention was given nine months starting on 4 July 2021 with a three month extension to come up with - from scratch - a brand new Constitution which then would be later voted on again in another plebiscite by the voters. The 154 member group consisted of members from the large variety of Chile’s political parties and activist groups but also required gender parity, reserved seats for certain indigenous groups and required a 2/3 vote to advance any draft. These individuals were voted in during a complicated election process (43% voter turnout) earlier in the year after being postponed several times due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

A draft of the proposed Constitution was first made available to the public in May of 2022 and once the Convention ended in July, the final draft made available. (English translation). It’s a whopping 178 pages long with 11 chapters and 388 articles. It’s seven times longer than the US Constitution and even longer than the Chavez-written Constitution that help sink Venezuela. The Economist describes it as a “fiscally irresponsible left-wing wish list,” and even uses a hilarious graphic of a toilet paper roll for the illustration in their article.

The Havana Times, of which copies you can buy in Cuba with coins featuring our notable friend from earlier and LGBTQ hero Che Guevara, describes it as “The End of State-Sanctioned Heteronormativity.”

I describe it as “Woke and Postmodern Orwellian Gobbledygook.”

During the Convention’s drafting activities, former FECH leader Gabriel Boric won the 2021 Chilean Presidential elections. He ran on a far-left platform and indicated he was in favor of replacing the constitution. Boric took office in March stating he wanted to “bury neoliberalism” and establish a Nordic-style welfare state. Boric is also “green” as someone who is excessively critical of the forestry and mining industries and takes climate change seriously. He also wishes to nationalize lithium mining and disapproves of a new copper mine.

Unfortunately for Boric, he doesn’t have a majority in Congress which keeps him from going too crazy with his desired agenda. His popularity has waned during the first few months of his time serving as President in part due to record inflation, increasing energy costs, and record crime7.

IV. An Uncertain Future for The Dual Transition

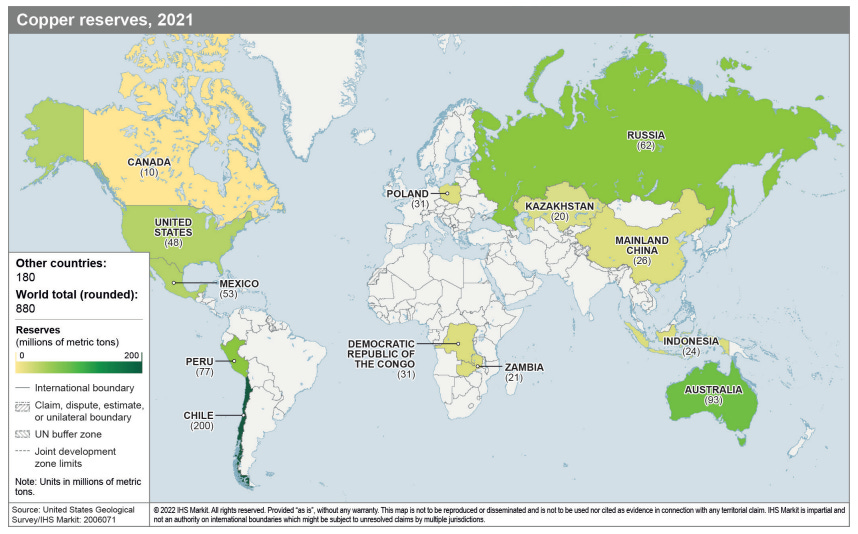

Today, Chile is the world’s largest miner, exporter, and second largest producer of copper, which contributes to roughly 20% of the country’s GDP, and 60% of her exports. Any large fluctuation of copper on the global market causes the national currency, the Chilean Peso, to rise or fall in unison. Copper is often referred among Chileans as “el sueldo de Chile, “ or “Chile’s salary.” The country has even been labeled as having the infamous Dutch Disease due to its heavy reliance on the metal for its economy. Copper, among those in the commodity trades, is also called Dr. Copper for its cyclical nature is often a good predictor of upcoming economic downturns

CODELCO, the State’s phenomenal little money minter, alone roughly accounts for 30% of all of Chile’s copper production or a whopping 8% of global production, the company has the largest copper mining operation and largest known reserves among its properties. While Chilean law (currently) leaves ownership of all minerals in the nation to the State, the remaining 60% of Chilean copper mining and production is left to concessions (setup during the Pinochet era as part of a partial denationalization process) who composes of multi-national mining firms such as the behemoths BHP and Rio Tinto as well as smaller Chilean firms.

The Chilean copper (and other important mining) industry faces issues both from Boric if he gets his way AND from the proposed Constitution. The Convention at one time even debated including full nationalization Venezuela-style of nearly all of Chile’s mineral resources including copper, lithium, hydrocarbons, and precious metals. Boric has indicated he wants to establish a State-owned lithium mining firm.

As noted earlier, the proposed Constitution is insanely long, long enough that it’s doubtful most voters have even read it. Also, highly doubtful is whether any of the English-speaking Corporate Press or the left-leaning progressive/woke activists cheering it on in the English-speaking world have either.

It’s also chock full of easy to misinterpret statements, lacks definitions, contains contradictions, repetitions, and a fair share of items that could spell doom many things but I wish to focus on the country’s copper and other extractive industries.

Take for example, that the Constitution grants rights to nature:

CHAPTER II. FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND GUARANTEESArticle 103.

1. Nature has the right for its existence, regeneration, maintenance and restoration of its functions and dynamic equilibrium, including natural cycles, ecosystems and biodiversity to be respected and protected.

2. The State must guarantee and promote the rights of nature.

In fact, Nature’s rights are so important, it’s essentially repeated again in the next Chapter under Article 127:

CHAPTER III. NATURE AND ENVIRONMENTArticle 127.

1. Nature has rights. The State and society have the duty to protect and respect them.

2. The State must adopt an ecologically responsible administration and promote environmental and scientific education through permanent training and learning processes.

As expected, the woke Orwellian gobbledygook is ever present:

Article 128.

1. The principles for the protection of nature and the environment are, at least, those of progressivity, precaution, prevention, environmental justice, intergenerational solidarity, responsibility and fair climate action.

2. Whoever damages the environment has the duty to repair it, without prejudice to the corresponding administrative, criminal and civil sanctions in accordance with the Constitution and the laws.

It makes specific reference to “climate and ecological crisis”

Article 129.

1. It is the duty of the State to adopt actions for prevention, adaptation and mitigation of risks, vulnerabilities and effects caused by the climate and ecological crisis.

2. The State must promote dialogue, cooperation and international solidarity to adapt, mitigate and confront the climate and ecological crisis and protect nature.

Things get really interesting for mining and extraction of minerals, ores, or hydrocarbons.

Mineral StatuteArticle 145.

1. The State has absolute, exclusive, inalienable and imprescriptible dominion over all mines and mineral substances, metallic, non-metallic, and deposits of fossil substances and hydrocarbons existing in the national territory, with the exception of surface clays, without prejudice to the ownership of the land on which they are located.

2. The exploration, exploitation and use of these substances shall be subject to a regulation that considers their finite, non-renewable nature, intergenerational public interest and environmental protection.

Article 146.

Glaciers, protected areas, those established by law for reasons of hydrographic protection and others declared by law, are excluded from all mining activities.

Article 147.

1. The State must establish a policy for mining activity and its productive chain, which will consider, at least, environmental and social protection, innovation and the generation of added value.

2. The State must regulate the impacts and synergic effects generated in the different stages of the mining activity, including its productive chain, closure or stoppage, in the manner established by law. It is the obligation of whoever carries out the mining activity to allocate resources to repair the damages caused, the environmental liabilities and mitigate its harmful effects in the territories where it is developed, in accordance with the law. The law will specify the way in which this obligation will apply to small-scale mining and pirquineros.

3. The State shall adopt the necessary measures to protect small-scale mining and pyre mining, promote them and facilitate access to and use of tools, technologies and resources for the traditional and sustainable exercise of the activity.

“Environmental democracy” (whatever that means) is also guaranteed by the state.

CHAPTER IV. DEMOCRATIC PARTICIPATIONArticle 154.

1. It is the duty of the State to guarantee environmental democracy. The right to informed participation in environmental matters is recognized. The mechanisms of participation will be determined by law.

2. All persons have the right to access environmental information in the possession or custody of the State. Private parties must deliver environmental information related to their activity, under the terms established by law.

And speaking of Nature, the magazine that is, who have notoriously gone off the deep end into full blown woke ideology, insists the new Constitution is “rooted in science.”

Among other things, the President would now be allowed to run for a second four-year consecutive term, the Senate would be abolished; and to guarantee all these rights and privileges the Chilean State must not only bring in sufficient revenue (or hyperinflate the peso) but also balloon the size of the state into an ever larger bureaucracy than it already is. Chile is currently a unitary state with excessive amounts of centralization. Latin America isn’t exactly a Mecca for stable governments or true democracies yet Chile has been a notable exception on many fronts since 1990’s return to democracy.

The 1980 Constitution, even though it’s been amended nearly 70 times since the return to democracy giving it the label of Lagos Constitution (after former President Ricardo Lagos), is far from perfect but it’s also not nearly as “rooted in Pinochet” as the opponents say it is. Anybody whose dipped their toes into Chilean politics understands this is an extremely touchy issue. (Disclaimer: I lived and studied in Chile roughly a decade and a half ago. Believe me when I say it was good preparation for the notorious division we see here in the US nowadays)

But like it or not, mining is a part what makes the modern world tick. Copper, in particular, is vital for a long list of items and demand for it is set to increase especially with the demand for net-zero/decarbonization pipedreams, renewable energy projects, EVs, the continued electrification of the unempowered world and the all-electrification fantasies in imbecile run asylums like California.

Copper extraction also takes a heavy toll on the environment and if not done correctly and responsibly also poses a hazard to those who work in the mines and smelter but also to those who live nearby. If Chile does succeed in approving this new Constitution, it’s almost a guarantee it will gut the copper and other mining industries inside the country. Such an event would prove catastrophic to those employed in the industry, to Chile’s economy, and government revenues. The rest of the world could be heavily restricted or cut off of the largest source of copper.

Chile right now is in the crosshairs of two transitions: the transition to what many see as a new chapter for the country but also the global energy transition which she will ultimately influence.

Right now current polls suggest Chileans more likely to vote “no” this Sunday.

We’ll see.

Both Fuser and Alberto eventually wrote their own separate accounts of their trip, one being called Diarios de Motocicleta (Motorcycle Diaries) by Che himself, and the other Con el Che por Sudamérica (Traveling with Che Guevara: The Making of a Revolutionary). The former was made into a highly successful film in 2004.

Che was also an admirer of Mao, the architect of the Great Leap Forward. Seems both really liked fast-moving utopian ideas that killed or infringed on the rights of lots of people. Go figure. He was also a cold-blooded killer, notoriously racist, and homophobic, but that doesn’t stop millions of people (outside Cuba) from voluntarily wearing that famous shirt, quoting him, being the center of hip college concert venues, or worshipped by the greatest source of morality of all time, Hollywood.

As opposed to, who knows, maybe the rapid development of even his own country which at the time was fairly wealthy by Latin American standards?

Famous Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, a prominent and outspoken Communist Party member, fled the country in exile.

Such “bragging rights” leave out the fact he elected on an extremely narrow margin in the popular vote which had to be resolved by the Congress who demanded he sign what was essentially an affidavit confirming his allegiance to “democracy” in Chile.

Pinochet’s troops rounded up, imprisoned, tortured and killed thousands of Chileans. The whereabouts of some of the disappeared remain unknown to this day. While some of the soldiers involved were eventually brought to justice, Pinochet never really faced any consequences. Ironically many of the same people who chastise the human rights violations of Pinochet are silent to Castro’s in Cuba which were exasperated by Che when he was there.

I disagree with Boric’s politics immensely yet I’ll extend him some credit for rightfully seeing Chile is no perfect place. Like Che, I think he has some grossly unrealistic expectations and unrealistic solutions but unlike Che, I don’t think Boric is inherently evil or will turn into a cold-blooded killer.