Fossil Fool, Part II

Real Price Controls and (Windfall Profits Taxes) Have Never Been Tried

This Part II, please read Part I first if you have not already.

III. Insanity is Trying the Same Things Over and Over Again

From the earliest times, from the very inception of organized government, rulers and their officials have attempted, with varying degrees of success, to “control” their economies. The notion that there is a “just” or “fair” price for a certain commodity, a price which can and ought to be enforced by government, is apparently coterminous with civilization. For the past forty-six centuries (at least) governments all over the world have tried to fix wages and prices from time to time. When their efforts failed, as they usually did, governments then put the blame on the wickedness and dishonesty of their subjects, rather than upon the ineffectiveness of the official policy. The same tendencies remain today.

-Excerpt from Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls: How Not to Fight Inflation by Robert L. Scheuttinger & Eamonn F. Butler

President Biden’s speech last week didn’t highlight any specifics on how he wishes to address what he labeled as war profiteering on behalf of oil companies. Nor does he really have to, and it’s also not really his job to do so - that’s for Congress to do. (And he correctly sees that, or at least his advisors and speech writers do) In all reality, this is most likely just a political op designed to pump enthusiasm into the voters in the upcoming midterm elections taking place as the metaphorical ink dries on this piece.

But for those who want to take him seriously (myself included) it’s worth diving into what has been done in the US in the past. If Congress is to do anything (spoiler alert, they likely won’t, even when they’re controlled by the President’s own party), they’d likely look at two proposals: a tax on windfall profits or price controls. The former is hard to pin an exact definition as to what’s seen as a windfall (aka excess) is a bit of a value statement. Some loons might propose an export ban or even full blown nationalization.

The threat of windfall profits taxes and price controls comes up nearly every time oil prices (and thus gas prices) are seen to be higher than usual. In fairly recent times, this came up in the early 90s during H.W. Bush administration , the mid 00’s during W. Bush’s administration, and prior to the 2008 Financial Crisis when oil prices hit their record highs. Then Presidential candidate Barack Obama even made a specific campaign promise to implement a windfall profits tax on oil companies and with these monies he pledged to provide individual taxpayers with $500 and married couples with double that amount. This promise, unsurprisingly, was marked in Politifact’s Obameter as promise broken. I’m probably leaving off at least a few other examples in this century alone.

But perhaps the most interesting time to view what price controls and windfall profits taxes can do is to look at the last major energy (and inflationary) crisis to hit the US: the 1970s.

But first a bit of Business School 101.

Not because readers here need it (our regular audience might want to skip this but), but because any lurking politicians, bureaucrats, or elite corporate journalists are likely to need the remedial lesson. There are plenty of others out there who probably need the refresher too given how popular economic intervention is during energy and inflationary crisis.

V. Signals

I’m not sure understand the argument for a windfall profits tax on energy companies. If you reduce profitability, you will discourage investment which is the opposite of our objective. If it is a fairness argument, I don’t quite follow the logic since even with the windfalls Exxon has underperformed the overall market over the last 5 years. - Larry Summers

A common frustration among road users, whether they be motorists, cyclists, or pedestrians is one or more of each party on the road not communicating their intentions clearly which often results in a chain of miscommunication and misunderstanding. At best, it’s just a minor annoyance, and at worst it may result in a collision that can result in injury or even death.

Perhaps the most common complaint pertains to motorists is not using turn signals to indicate the desire to change lanes or make a turn. It is indeed frustrating because the use of such phenomenal technology carries an extremely small penalty for the motorist in the form of a minor cognitive load. It’s equally irritating when a motorist leave his or her turn signal turned on despite not changing lanes or making a turn.

Humans are social animals who rely on communication and cooperation. Just as turn signals and hazard lights are a tool, or uh, a signal, for one motorist to communicate to others likewise so are prices and profits. These all communicate information between individuals which empower them to make a decision. Markets (ideally) work in much the same way.

Not using theses signals when needed, using them when they’re not needed, or intervening in their use creates distortions and confusion.

Take any company, say Apple - who sells products such as computers, phones, and other consumer electronics along with services such as streaming subscriptions and software. The money Apple brings in via the sales of these products and services is referred to as their revenue. But Apple didn’t just get these products and services out of thin air- they cost them something to produce, which is cost of revenue. That difference - between revenue and cost of revenue (also sometimes called cost of sales since they directly impact the services and products) is their gross profit. But there is also a cost for running Apple’s business activities unrelated to the direct production of the goods and services - they must pay rents or mortgages, salaries and pensions for their employees, administration, marketing, etc. This is referred to as their operating expenses (or overhead). Subtracting these operating expenses from the gross profit provides the operating profit (oftentimes called operating income, yes I know - confusing AF). From here is where businesses pay whatever the governments demand they pay in taxes. Whatever is left over from that is their net profit.

Visually, here’s an example (TIL it’s called a Sankey Diagram) for Apple’s fiscal year 2022.

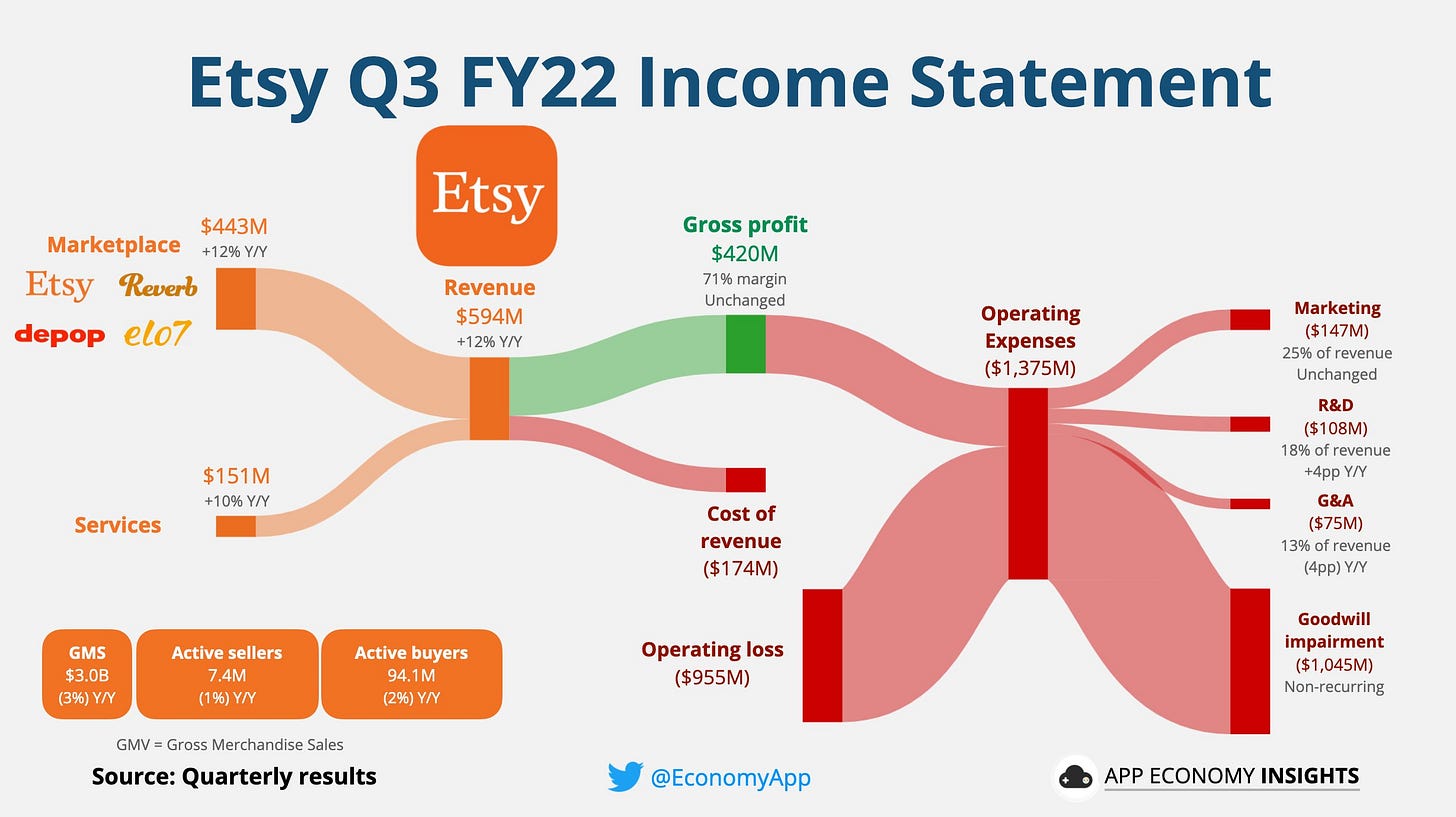

Here’s Etsy, who after accounting for all their operating expenses, did not realize any profits.

For the consumer, a business with high profits may not mean that much, perhaps that they’re an indication the business is being run well and may be around in the long term - sort of important for many purchases such as cars where servicing, parts, and warranty work may be needed later in the product’s live. (It could also mean they’re laundering money or cooking the books somehow. It’s happened before. But we’re going to assume the businesses here are engaging honestly until there is evidence to prove otherwise. Something something “due process”)

To investors, which differ form speculators by the way, profit often communicates that the business is being run competently and may be around for the long run. A company with good and steady profits is typically seen as a good investment. For business owners and operators, profits communicate they’ve successfully set the prices of their products and services to create the needed sales and that their expenses are low enough downstream to see the profits being realized. Investors are essentially loaning their money to these businesses and wish to see a return on that investment. Only a successful and profitable company can deliver those returns.

Nothing motivates incremental production like the threat of seizing profits directly from the risk takers needed to fund it. Nationalization can’t be much further over the horizon.

- Doomberg

It should also be said that profits are also a sign of a business’ (and investors’) willingness to take risk too. As the cliché goes, “higher risk = higher reward.” Many of the businesses that make eye-popping profits, or to be specific high profit margins, are engaged in higher risk activities. These same high risk activities often result in eye-popping losses as well. (This was seen across most of the energy industries in the few years leading up to the COVID 19 pandemic/ lockdown mania) A lack of profit in the short term may just be a blip, but a lack of profit in longer term often indicates something’s wrong somewhere in the business. Or to be more specific, either the capital or the labor that goes into the business is being poorly allocated.

President Biden in his speech earlier this week focused on what he labeled as both “record” and “excess” profits. It’s not difficult to figure out whether in a individual business has seen record profits - profits from past quarters or years can be compared to today. These data are available on nearly every financial media website from Morningstar, Yahoo Finance, MarketWatch, WSJ, and most notably every company maintains an investor relations type page on their websites with this information. Even silverspoon-fed (ironically, courtesy of Getty Oil) Gavin Newsom figured it out - or maybe one of his aides did.

Excess profits on the other hand are an entirely different animal as that’s a term in the eye of the beholder, and in the case of performative politics, means essentially anything the politicians feels they should mean.

Price control or fixing can take two different forms: above-market price fixing, and below-market price fixing. The former typically comes in the form of subsidies and the latter with caps and schemes such as rent-control. Below-market price fixing paradoxically increases demand for the product or service facing the cap because the price is kept artificially low. Eventually the supply becomes reduced, often significantly leading to shortages but also because the profit incentive for businesses (and investors) has either been reduced or removed. Smaller and marginal producers also tend to be driven out of business (spoiler alert!) or forced to merge with larger producers leading to consolidation and in some cases a duopoly or monopoly situation.

IV. The 1970s: Disco Gold Standard is Dead

“Everybody knows oil’s price. To understand oil’s value, fill your car up, drive it until it’s empty, then push it back to where you started it from.” - Luke Gorman

Before jumping right into the 1970s, we have to back up a bit- to 1959.

The US had a large oil industry yet also relied on import from other nations, namely Mexico, Canada, Venezuela, and a few of the big players in the Middle East. President Eisenhower in 1959 slapped import tariffs on some foreign oil as an effort to protect domestic production, “for the sake of national security” as in his view the US needed to be as close to self-sufficient as possible These tariffs capped oil imports at 12.2% of domestic production but exempted Canadian and Mexican oil shipped overland. By the early 1970s foreign crude prices reached near parity with US domestic crude prices making the scheme largely moot.

On August 15 1971, President Nixon addressed the American people. Facing increasing inflation, domestic budgetary issues, and the ballooning costs from the Vietnam War all of which he mostly reduced to “defending the dollar against money speculators” (which were really parties wanting to exchange dollar for ever larger amounts of gold) President Nixon announced a temporary suspension of the US dollar’s convertibility to gold and thus the peg of many major foreign currencies to the fabled greenback also known as the Bretton-Woods System. Over fifty years later, the US dollar remains what’s known as a fiat currency - one whose value is not tied to any hard asset and whose supply can be expanded by central banks on a whim. So much for temporary. The consequences of this decision go far beyond the scope of this writing.

In the same speech, he proposed a three month freeze on prices and wages, extra tariffs on imports, and tax cuts. When the 90 day period was over, all future price and wage freezes were to be approved by the “Pay Board” and “Price Commission.” These controls, all examples of below-market price fixing, were all stopped after the 1972 election where Nixon won his second term in a landslide against Sen. George McGovern. It after all appeared as if his efforts indeed did do something, which is typically a mirage seen in the short term.

Inflation didn’t cease though, in fact it got worse and it’s not as if there was nobody to warn them at the time such a thing would occur. Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman labeled these efforts once they ended in 1972, “an utter failure and the emergence into the open of the suppressed inflation.” Naturally this inflationary pressure already affected energy prices too.

In 1973, the Nixon Administration asked oil companies to allot certain amounts to refiners and ultimately service stations based on the previous year’s summer driving season instead of the actual current demand. This allocation scheme didn’t work as demand wasn’t addressed to the prices remained low which hampered on the need to increase supply. Ultimately it was the independent gas stations - the ones not owned by the major oil companies, who were short-changed an allotment because the oil companies prioritized their own branded service stations first. When shortages did hit, many of these independent stations were forced out of business. Nixon also ordered gas prices to be frozen in June of 1973 for two months, then in August followed up with a price freeze indefinitely.

In October of 1973 (shortly after one notorious event in Chile discussed here) in response to the Yom-Kippur War, the Arab nations who were members Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposed production cuts and export limitation to countries who supported Israel. Coupled with a dollar with declining purchasing power, oil prices began to spike more than they previously had and by November the Nixon Administration was getting extra nervous.

There were rumors about terminating the 1959 import quotas but it wasn’t until the month following the war the terminations occurred. They were replaced by a two-tiered tariff system with one based on “old” oil and the other on “new.” Nearly stripped domestic wells composed of the “old” oil, newly drilled domestic wells and imports composed the “new.” Supposedly this arcane system would limit windfall gains for the already existing producers (the “old”) and level the playing field to allow the “new” to compete. Ultimately this system led to a bungled mess with hundreds of companies popping up whose sole role was to pass the oil or oil-derived product from one party to another while charging a small markup each step of the way. Naturally all these markups, along with the higher price of oil itself were passed down onto the consumer. Economist Bob Murphy goes into more detail about this so-called “daisy chain” scheme in his article “Removing the 1970s Oil Price Controls: Lessons for Free-Market Reform” published in the Journal of Private Enterprise. It’s a mindboggling read.

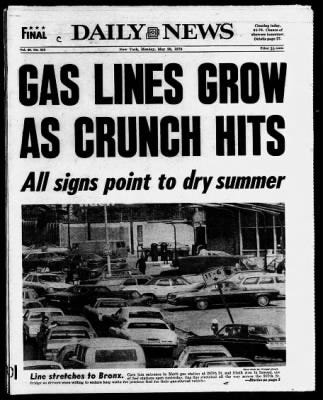

Just as OPEC was rolling out their production cuts, which have been forever cemented in history as an embargo, the oil companies in the US posted record profits for most recent quarter. Sound familiar? The excellent oil expert / historian Dr. Ana Alhajji recently dug up a Wall Street Journal piece covering this exact story.

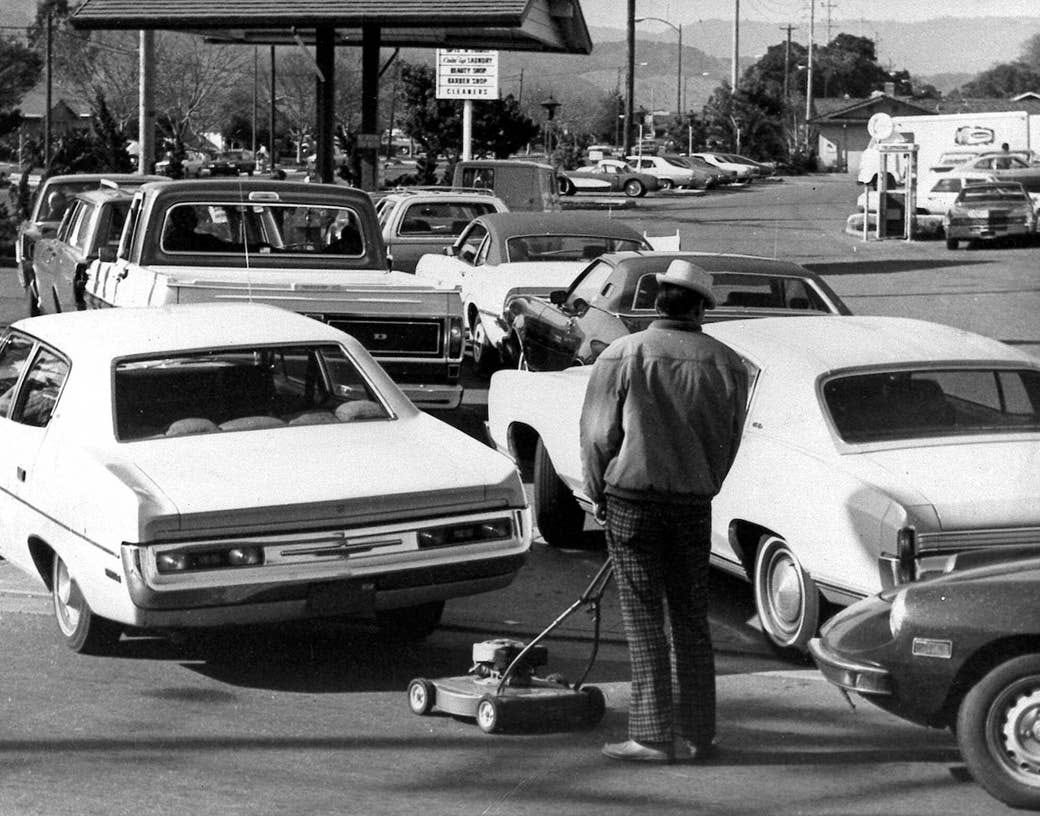

At the same time, the infamous long gasoline lines, shortages, and in many states, rationing typically based on the motor vehicle’s license plate. Oregon began with an optional program, followed by several states in the Northeast including New York and New Jersey. Some stations would sell until they ran out of supply and then close for the day while others sold a capped amount to each customer.

There were talks of a federally mandated program but it never arrived. Ration books were even printed by the US Bureau of Engraving and Printing in anticipation of such a program.

Ultimately, these rationing schemes coupled with price caps did little to actually reduce the demand, instead they simply made motorists often visit multiple gas stations to fill their tanks. Prices also jumped.

Oil prices by the start of 1974 increased 4x but the price controls set by the Nixon Administration prevented the market to properly function. Shortages, long lines, and the state-level rationing programs continued. The winter created a new problem: should refiners manufacture gasoline for motor vehicles, or heating oil for homes? This spurred a crisis especially in New England, which doesn’t exactly experience mild winters but also is (and remains to this day) heavily dependent on heating oil.

Deja Vu all over again:

Diesel fuel, used far less by every day motorists but vital for trucking and agriculture did not have as many restrictions but did face steep price increases. Truckers nationwide went on strike for days at a time though to protest the prices. Some of the strikes resulted blocked highways and some of the protests even turned violent.

A recession eased some of the demand, and the Arab OPEC member states eased off and eventually ended their embargo. The price caps on gasoline and rationing were also terminated although caps remained on crude oil itself but the decreasing prices made it somewhat moot. The infamous national 55mph speed limit was enacted in 1974. The Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards (CAFE) were also developed and became a legal requirement for automobile manufactures starting in 1975. President Nixon resigned in the September 1974 after the Watergate Scandal stole the country’s attention.

His predecessor, President Ford, had things a bit easier for him on the energy front although he was still dealing with what became to be known as stagflation, higher than usual unemployment, and a sluggish economy. Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter won the 1976 Presidential elections and was sworn in in early 1977. The next year the Strategic Petroleum Reserve was conceived and in 1977, a new executive level cabinet, the Department of Energy, was created to foresee and manage the country’s energy needs. For a brief time, daylight savings was even extended year around.

The energy crisis returned with a vengeance in 1979 during the Iranian Revolution which overthrew the Shah. At the time, Iran was a large oil producer but after the Revolution their exports at one time decreased to zero. The shortages only amounted to roughly 5 or 5% of global production but it was a panic that set the prices to sour even more than in the 1973 crisis. Along with the still in effect price controls in the US on crude oil price increases and panic sparked a second wave of shortages, long lines, and rationing. The Federal Government once again considered rationing as well, to the point of printing ration books just as they did under the earlier energy crisis but ultimately never used them. Motorists also began to keep stockpiles of gasoline, often at home (usually in their garage) causing concern for fire departments. Service stations often imposed a minimum purchase requirement to prevent customers from purchasing small amounts for the purpose of simply topping off their tanks. The trucker strikes also returned.

President Carter asked Congress to remove the price controls apparently understanding that the best way to get people to reduce their consumption is to be faced with appropriate price signaling. To dampen the political implications given that consumers would likely not be happy with increasing prices he also asked for a tax on oil company profits. In 1980 he signed the Crude Oil Windfall Profits Tax Act into law. Despite the name of the law (sound familiar, “Inflation Reduction Act” anyone?) , it was not a windfall profits tax, it was instead a 70% excise tax. Said tax was only on oil sold above $12.81 per barrel or $46.14 in 2022 dollars The monies collected were to be used to fund the research and development of alternative fuels and renewable energy projects - an example of above-market price fixing or otherwise known as subsidies. (Strangely enough, he seemed to sort of understand basic economics when he signed the laws allowing deregulation of the airline industry.)

Furthermore, the tax only applied to domestic oil producers. Predictably, the scheme dampened domestic oil production while increasing the US reliance on imported oil, and it did not bring in the revenues expected and/or “promised” by the bureaucrats and politicians who sold the idea. In his 1980 campaign, Presidential Candidate Ronald Reagan promised to repeal the taxes but it ultimately did not occur until his second term in 1988.

Stay Tuned for a Part III where we finish of some loose ends such as subsidies such as Strategic Midterm Petroleum Reserve, export bans, and nationalization.

Quite new to you but i absolutely love these posts. Unfortunately your work is a little like Irina Slav's - fantastic but equally scary. What you both show is that Western politicians (I'm in the UK) refuse to learn from the past and will stop at nothing to deceive us and bring misery to our lives.

Good read! You might enjoy this perspective as well.

https://finiche.substack.com/p/portfolio-insights